The roots of Abiy’s anti-Wallaga bias

Abiy Ahmed’s negative perception of Wallaga is deeply rooted in the historical relationship between the Oromo and the Ethiopian state.

Subscribe to Curate Oromia.

Find out about our latest articles, calls for submissions, and other updates.

Hopes for peace, unity and development as a new Abbaa Gadaa takes power

As the Borana and the Oromo people welcome this new era of leadership, they hope his term will bring peace, unity, and development.

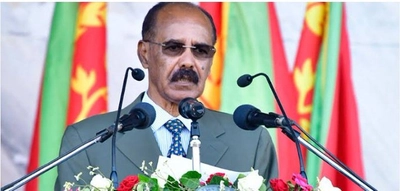

Ethiopia’s Necropolitical Turn

Under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia, the distinction between war and politics has blurred.

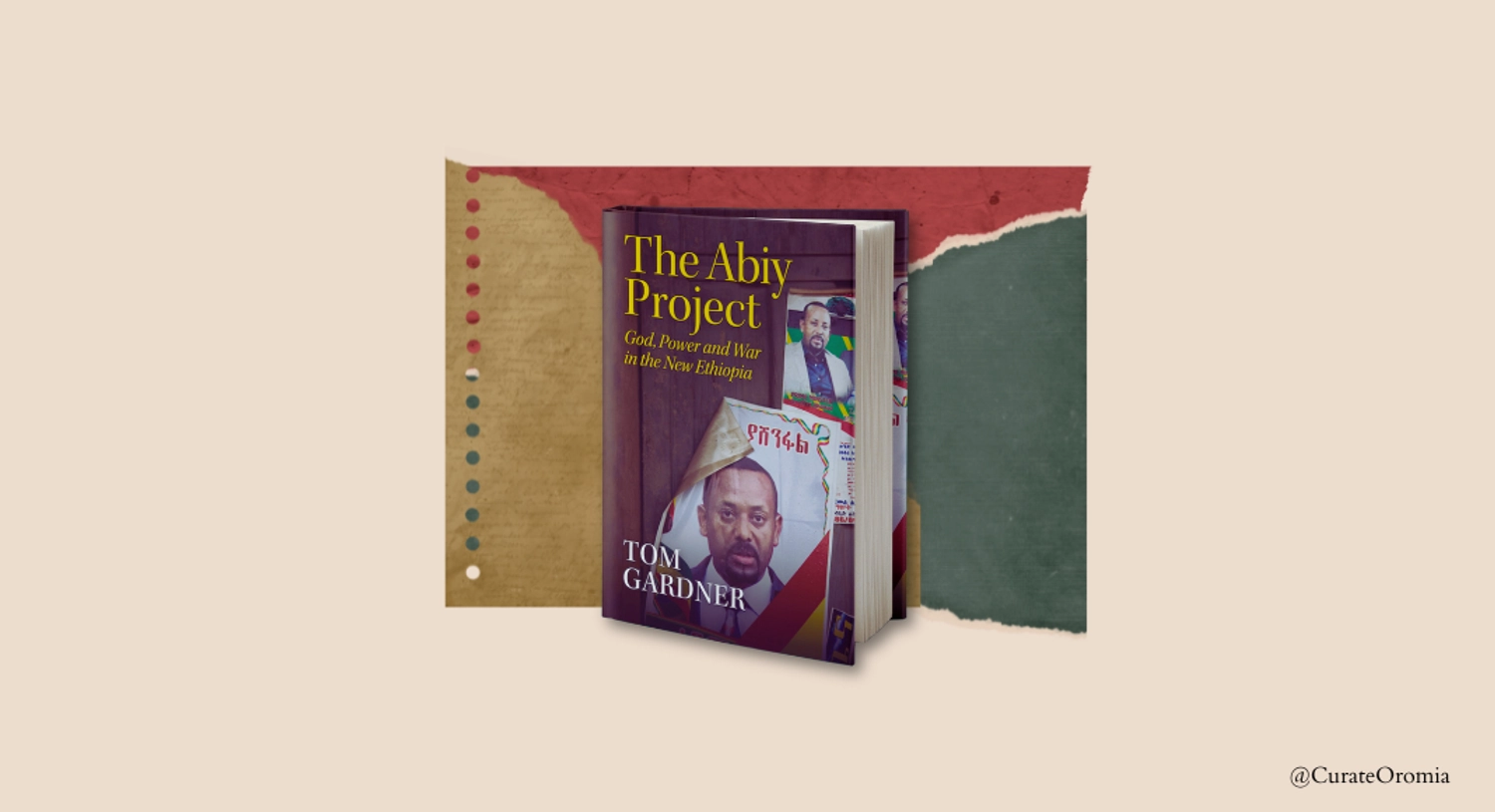

The Abiy Project: A conversation with Tom Gardner

Abiy is an idiosyncratic Ethiopian nationalist first.

The roots of Abiy’s anti-Wallaga bias

Abiy Ahmed’s negative perception of Wallaga is deeply rooted in the historical relationship between the Oromo and the Ethiopian state.

We rely on your support.

Our mission is to tell Oromia’s stories on their own terms. Running an independent platform has significant challenges, but readers like you keep us going. Every contribution, however modest, goes directly to our writers and the expansion of our work.