Conceptualizing the Images of Girls in Guji Oromo Proverbs

By critically engaging with proverbs, retaining those that affirm care, cooperation, and responsibility while abandoning those that naturalize inferiority, Guji society can transform its oral heritage into a tool for gender equity.

Subscribe to Curate Oromia.

Find out about our latest articles, calls for submissions, and other updates.

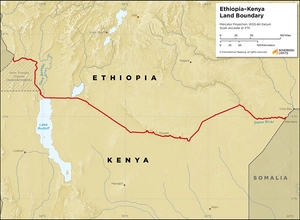

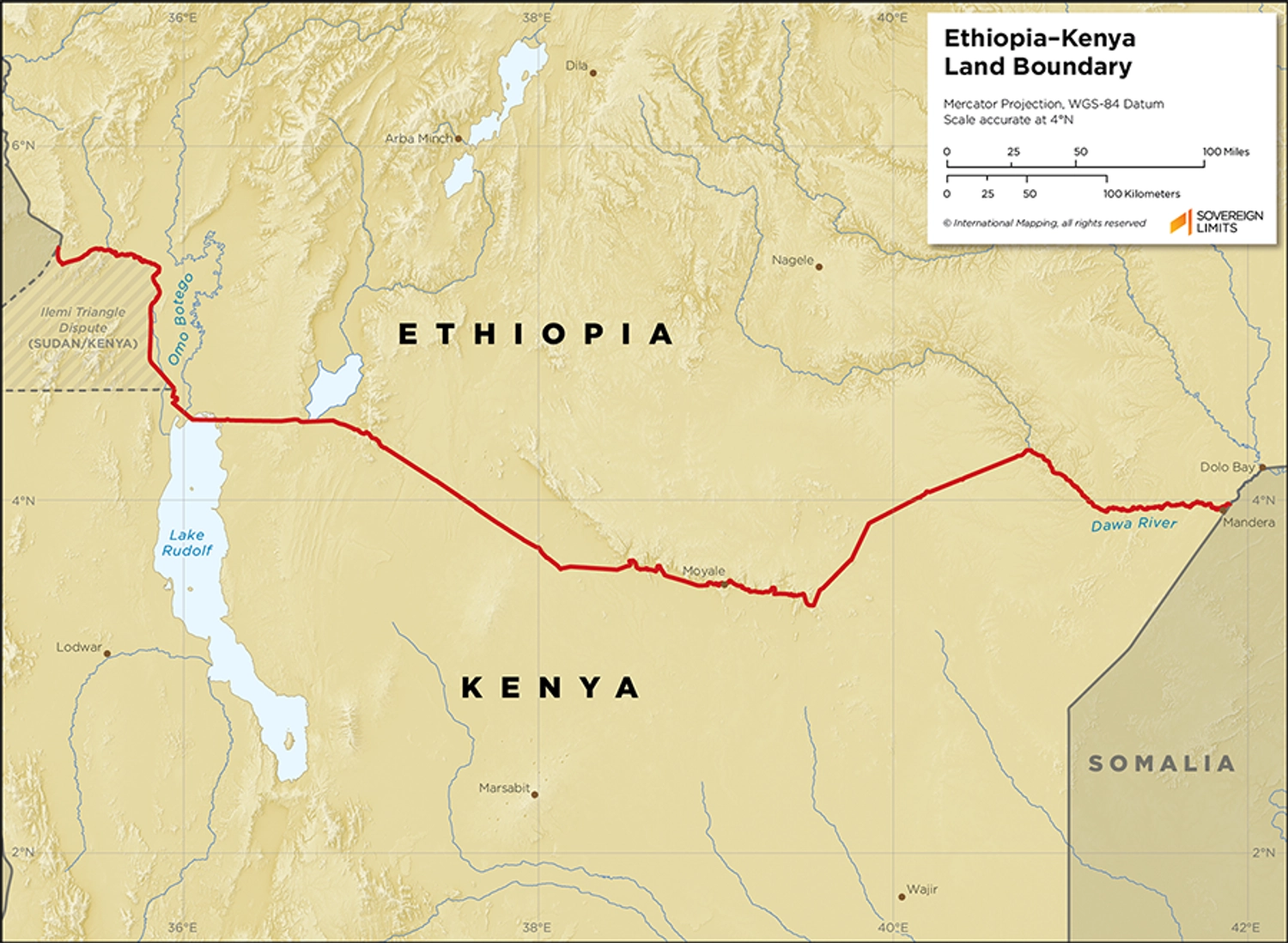

Kenya’s extrajudicial killings, abductions, and torture in Moyale spark protests

“We want the government to tell us whether we are Kenyans or not.”

Conceptualizing the Images of Girls in Guji Oromo Proverbs

By critically engaging with proverbs, retaining those that affirm care, cooperation, and responsibility while abandoning those that naturalize inferiority, Guji society can transform its oral heritage into a tool for gender equity.

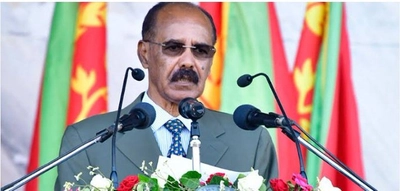

The Abiy Project: A conversation with Tom Gardner

Abiy is an idiosyncratic Ethiopian nationalist first.

Irreecha Nairobi: A New Dawn for Oromo Unity in Kenya

The Oromo community of Kenya celebrates Irreecha 2025 at Uhuru Park in Nairobi on October 25, 2025. Photo: Social Media.

We rely on your support.

Our mission is to tell Oromia’s stories on their own terms. Running an independent platform has significant challenges, but readers like you keep us going. Every contribution, however modest, goes directly to our writers and the expansion of our work.