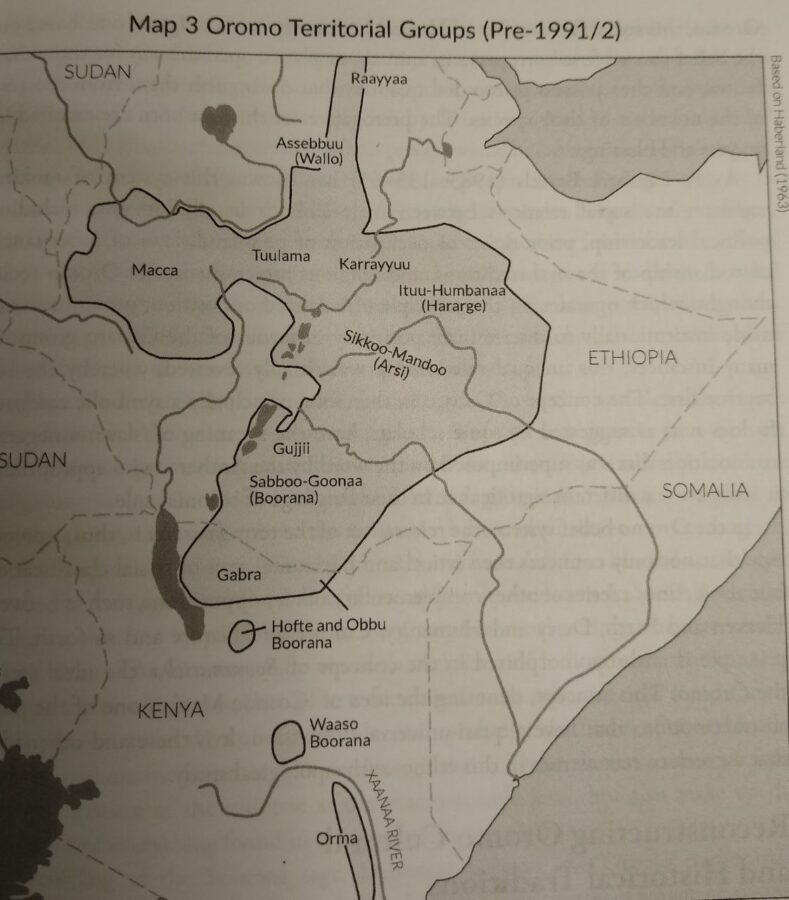

Oromos are Africa’s second-most populous ethnic group and the largest in the Horn of Africa. Primarily native to Ethiopia’s Oromia region, they also exist in minority populations in Kenya, specifically in Marsabit, Isiolo, and the Tana River Basin. Kenyan Oromos, who include the Borana, Gabra, Orma, and MunyoYaya, number close to a million.

The Borana

The Borana reside in northern Kenya, the Marsabit and Isiolo counties, and the southern Oromia region.

They are primarily pastoralists who raise cattle, sheep, and goats and engage in small-scale farming on fertile lands in the higher regions surrounding Moyale and in river basins in Isiolo County. The Borana in Kenya have always practiced the Gadaa system, which served as the guardian of their identity.

The Gabra

The Gabra are the second Oromo group in Kenya, and like the Borana, they keep cattle in the highland parts of their territory and raise camels in the lowlands. This livestock specification is one point of ideological differentiation that separates the Eastern Cushitic Gabra from their closely related Borana; the Gabra depend mainly on camels, while the Booran are cattle people.

The Gabra occupy territory east of Lake Turkana in western Kenya, the Bule Dera plain in the east, the Mega escarpment in Ethiopia to the north, and an ill-defined southern limit running from the Marsabit highlands northwest across the Chalbi Desert towards the Chari Ashe hills extending to Ethiopia. The Gabra are expert resource managers and as such, they migrate to the highlands during the rainy season to allow the dry season pasture to replenish its water resources. In the highlands, they live most self-sufficiently, and ritual ceremonies abound. The timing of initiation rites, migrations, and birthing patterns of the Gabra are determined by the cyclical weather patterns and the pasture needs of their herds.

The Gabra know that to live in harmony with the environment, one must care for and preserve nature, animals, and one’s fellow Gabra. This dedication serves as the basis for the Gabra proverb “A poor man shames us all,” which is possibly the most symbolic phrase of the Gabra identity. Since mutual support is imperative for their survival as nomads, no Gabra may be allowed to go hungry, go without animals, or be refused hospitality or assistance. A person who refuses to help others is labeled “al-bokkuu,” a stigma that remains with the family for generations. The Gabra practice of camel lending is an excellent example of this support system.

The Gabra’s mixed-livestock economy is almost entirely based on reciprocity. A camel will be loaned or given to another Gabra in need, and a future act of reciprocity will be expected. In this sense, camels provide great security; they also provide most of the meat and are responsible for the milk supply in the dry season. In contrast to their sharing nature among each other, selling camels or their by-products to outsiders is something that is largely frowned upon in Gabra society.

The Orma

The Orma people are remnants of a powerful nation of Ethiopia and northern Kenya, and in the late nineteenth century, wars with neighboring tribes forced the Orma to migrate south. Some moved to the rich delta area of the lower Tana River, and others settled west of the river.

In the dry season, they live near the banks, and when the rains come, these semi-nomadic people move further inland to the west to escape the floods. The Orma are related to other Oromo people living in Kenya and share with them the Oromo language and cultural heritage. Like most of the Oromo people in Kenya, the Orma are pastoralists, and cattle are central to their culture. Over time, the Orma divided to form three sub-groups.

The MunyoYaya are part of the Orma people, but they consider themselves a separate tribe and are therefore labeled as a distinct ethnic group in Kenya. Numbering about 15,000, they live in the Tana River district, north of the Coast province, where they practice subsistence farming on the floodplains of the Tana river, growing corn and bananas. Though they keep some livestock, life on the Tana river has made fishermen out of the MunyoYaya.

One thing all these groups have in common is the river by which they have chosen to settle. The semi-arid Kenyan plains are traversed by the Tana River and its numerous tributaries and seasonal rivers over hundreds of kilometers. Kenya’s longest river makes an impressive journey, rising in the Aberdare Mountains west of Nyeri and running eastward before veering south around the massif of Mount Kenya. It then opens onto a wide valley, where it meanders through a floodplain often subject to its seasonal inundation, before it continues on its voyage towards the Indian Ocean. The river is known for the extraordinary biodiversity it sustains as well as the wildlife it supports. For the many branches of the Oromo people who have built their lives in the Tana River County, farming, livestock rearing, and existence, in general, depend on the river and the life it brings to the land.

The Waata are another Oromo-speaking people found beside the Lamu district along the Tana River in Kenya. The Waata are former hunter-gatherers, and to this day they consider hunting a divine gift, one whose values they continue to pass on to the younger generation. Wayyuu Banoo, the founder of the Waata and creator of their hunting tradition, is also credited with establishing the Qaalluu dynasty. The Qaalluu play an indispensable role in all life cycle and transition ceremonies among the Oromo people, including the Borana and the Gabbra.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Visit Oromia Magazine.