The Matcha-Tulama Self-Help Association (1963-1967) is a landmark in modem Oromo history; it was the first pan-Oromo movement that coordinated country-wide peaceful resistance, which gave birth to Oromo nationalism. The movement symbolized the collective will and firm determination of the Oromo to consolidate their unity and regain their freedom and human dignity. It exploded the Ethiopian ruling elites’ myth of Oromo disunity and demonstrated the vitality and depth of Oromo unity. The movement gave the Oromo freedom of the mind and the spirit, and a new sense of unity and nationhood. Since the 1960s, no force was able to kill the spirit of freedom, self-respect and human dignity which the Matcha-Tulama Self-Help Association implanted in the Oromo mind and the Oromo soul.

Although the association was mentioned in a number of writings, the first truly major work on the association is Olana Zoga’s Gezetena Gezot (Oath and Banishment), Matcha, and Tulama Self-Help Association. It is a remarkable book that depicts the activities of the association during its short existence, its leaders, their strength and weakness, the association’s achievements and failures, the callous disregard with which it was destroyed, and the lessons to be drawn from its experience. Anyone who is interested in understanding Ethiopian history in the 1960s in general and Oromo history, in particular, will be rewarded by reading this book which is a timely addition to the growing literature on Oromo studies.

Olana Zoga, the author of this balanced, authoritative, and comprehensive study on the Matcha-Tulama Association, is the son of one of the association’s founding members. The author, himself, was an activist in the Ethiopian University movement in the early 1970s. His command of the Amharic language is excellent. His fairness and objectivity in presenting contentious issues is impressive. He conducted oral interviews with the founding members of the association who are still alive, with a sincere desire to learn from their experiences. The result is this book, a path-breaking work on the history of the association.

So far, it is the richest, lucid, and beautifully written book on the formation, activities, and destruction of the Matcha-Tulama Association. The book is based on solid research coupled with interviews with the leaders of the association as well as with thirty other knowledgeable individuals (p.4).

According to the author, the book was written for four purposes. The first is to record and pass on to the next generation the long history of the Oromo struggle for human dignity, freedom, and equality. The second is to record the events of the 1960s so that we may learn from the mistakes of the period which would help us to build a better country in the future. The third is to record the Oromo people’s resistance of the 196Os, the causes for, and the ideology of that resistance. The final purpose for writing this book is to inform the present Oromo generation, which faces similar circumstances, of the intrigues and the political machination which destroyed the association in the 1960s. If the Oromo elites do not learn from the tragedy of the association, their fate in the 1990s will not be different from the fate of the leaders of the association in the 1960s.

The Formation of the Association.

Chapter one deals with “The Formation of the Association.” In this chapter, the author discusses the 1960 military coup against Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime, its aftermath, and the formation of the Matcha-Tulama Association. Although the 1960 coup failed in its main objective, it did shatter the myth of Emperor Haile Selassie’s invincibility and exposed the weakness of his regime. On the one hand, the 1960 failed coup sharpened the contradiction within the Amhara elite itself, while on the other hand, it deepened the conflict between the Amhara ruling class and the Oromo elite.

The contradiction within the Amhara ruling elite is succinctly expressed in a manifesto produced by military officers who planned another coup in 1961. The officers, who expressed the political view of the advanced section of the Amhara ruling elite, lost confidence in the leadership of Emperor Haile Selassie. Even more importantly, the officers challenged the fundamental policy of the imperial regime. For those officers, the concept of Ethiopia was much more than the political, economic, cultural, language, and religious supremacy of one ethnic group in the country. For those officers, especially lieutenant Beqele Sagu and Colonel Imru Wonde, who authorized the manifesto:

Ethiopia is the sum total of all its districts and people, while for our rulers Ethiopia means only the ruling class [i.e. the Amhara]. What is presented in the name of Ethiopian culture is the culture of the same ruling class [Amhara]. Whenever the issue of religion is raised, Ethiopia is presented as the land of only one religion [i.e. Orthodox Christianity]. Whenever the issue of language is raised, the existence of various Ethiopian languages is denied. [Amharic is recognized as the only language in the country] In the present condition of Ethiopia, the cultures, religions, and languages of our people are to be destroyed and replaced by the culture, religion, and language of the ruling class [i.e. Amhara], (p. 10).

The authors of the Manifesto not only succinctly express the reality of the Amhara ruling elites’ domination of the Ethiopian political landscape, but they also argue for ending national domination and establishing of a democratic structure that abolishes tenancy and ensures equality and economic opportunity for all the peoples of Ethiopia. The political view of the military officers of Oromo origin was partly shaped by the heightened tension within the Amhara ruling elite. It was partly a response to Emperor Haile Selassie’s new discriminatory policy. After the 1960 failed coup, Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime followed a secret policy of limiting the number of high-ranking military officers of Oromo origin and controlling their promotion. This policy not only angered many high-ranking officers of Oromo origin, but it also revealed the deeply seated anti-Oromo prejudice existing within the Amhara political establishment. Those officers whose cultural and ideological orientations would have integrated them “into the heart and the soul of the Ethiopian system”1 were all Orthodox Christians who were culturally Amharized.

They were loyal to the Emperor and were strong Ethiopian nationalists. Not a single high-ranking officer of Oromo origin supported the 1960 failed coup; on the contrary, they opposed it. Colonels (later Brigadier Generals) Taddesse Birru, Jagama Kello, Waqejira Serda, Dawit Abdi, and Major Qadida Guremesa (pp. 349, 352) supported the Emperor and they were instrumental in aborting the 1960 coup. Yet, they were suspected of disloyalty and subjected to discrimination. This policy not only angered Oromo officers but also encouraged them to be involved in political activities (p.12).

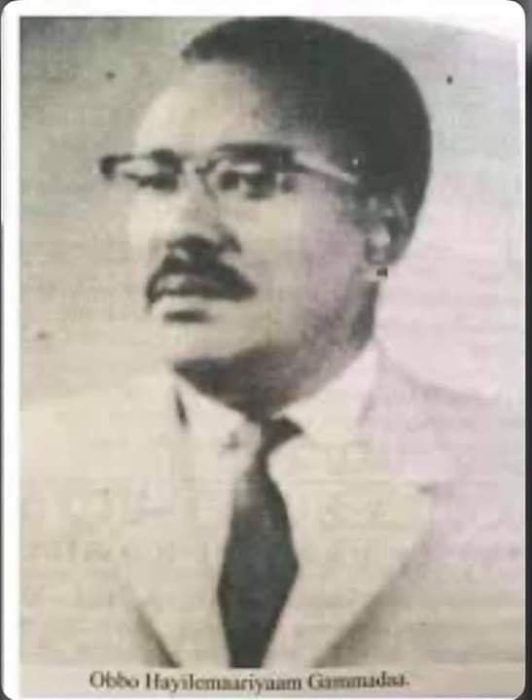

Colonel Alemu Qitessa, one of the founding fathers of the Matcha-Tulama Association, was among the high-ranking officers who was angered by the discriminatory policy of Haile Selassie. Another key founding father of the association was Haile Mariam Gamada, a man with an encyclopedic knowledge of Oromo history, a lawyer, and a greatly respected leader. He chaired the committee that drafted the by-laws of the association, coined the name of the association, and produced its logo: the odaa (sycamore tree), the symbol of freedom and self-administration (p.19).

The name of the association symbolized the unity of two major Oromo groups, that of the Matcha and Tulama, while its logo, the odaa indicates the desire for return to the original Oromo Gada democracy. Originally the Oromo believed odaa to be the most sacred of trees, the shade of which was the source of peace, the center of religion, and the office of government–the meeting place for the democratically elected gada leaders.

The association was formed on January 24, 1963. It had a policy-making board of thirteen men and seven committees. Colonel Alemu Qietessa was the President of the association and the Chairman of the Board; Beqele Nadhi was vice-president, Colonel Qadida Guremessa, the second vice-president, and Haile Mariam Gamada was general secretary.

The main objectives of the founders of the association were to mobilize and organize the entire Oromo people for educational growth, improvement in health conditions, and economic development (pp.15-16). The leaders of the association submitted their by-laws to the government for legal recognition. One year and four months later (i.e. May of 1964) Haile Selassie’s government gave permission for the association to function as a self-help organization. It was grudging recognition which the government officials later regretted (p.21).

Activities to Strengthen the Association

Chapter Two deals with the “Activities to Strengthen the Association.” According to the author, once the government permitted the association to function as a self-help association, its leaders started mobilizing the people for economic development through public meetings. The first large public gathering took place in the town of Ginchi in Jibat and Matcha Awraja (sub-province), followed by another gathering in the same Awraja in the district of Jeledu, where Colonel Alemu Qietessa gave 10,000 hectares of his own land for the association’s development activities (p. 24). Encouraged by promising development activities, Colonel Alemu Qitessa decided to invite prominent military officers of Oromo origin to join the association. The first to be invited was General Taddesse Birru, the Commander of the Rapid Force (riot battalion), the Deputy Commissioner of the national police force, the commander of the Territorial Army, and the Chairman of the national literacy campaign. General Taddesse Birru was the most powerful officer of Oromo origin, a rising star within the Ethiopian political establishment.

He was a deeply religious man who was assimilated into Amhara culture, spoke Amharic, and married an Amhara woman. He was an ardent Ethiopian nationalist loyal to the Emperor and integrated into the heart and soul of the Ethiopian system. When he was invited to join the association, his answer was “I cannot participate in tribal politics” (p 24). But to his credit, as the Chairman of the National Literacy Campaign, he promised to help the association in its mission to spread literacy. In those days the literacy campaign was conducted only in the Amharic language for the purpose of spreading that language into non- Amhara areas.

General Taddesse Birru not only enthusiastically supported the literacy program which would have facilitated the Amharization of the Oromo but also, he wanted to create an Ethiopian nation based on the equality of all Ethiopians. It was this officer who later became a militant Oromo nationalist, a symbol of courage and a great martyr. How did that happen? The story is long, and it is covered in several chapters. Here is how it started.

First, as a veteran of the anti-fascist resistance movement and an officer with long service both in the military and police forces, he was very popular in the Ethiopian political establishment. This popularity may have excited the ambition of the general and aroused the anxiety of Emperor Haile Selassie. Secondly, as a self-educated man, his love for knowledge and concern for the poor is admirable.

“He had an extremely pleasant personality and was liked by the rank and file in the army [and police]. He was kind and considerate and was always on the side of the disadvantaged. Because of his sympathy for the poor, the Amhara [leaders] feared him, but they thought he was an Amhara national who could not be very dangerous to their oppressive system.”2

Thirdly, General Taddesse Birru’s enthusiastic support for the spread of literacy among the Oromo alarmed the Ethiopian Prime Minister of the day, Akelilu Habite Wolde. The latter, who assumed General Taddesse Birru to be an Amhara, confided in him the educational policy of Haile Selassie’s government in these words:

Taddesse! After you have started leading the literacy campaign, you talk a lot about learning. It is good to say to learn. However, you must know whom we have to teach. We are leading the country by leaving behind the Oromo at least by a century. If you think you can educate them, they are an ocean (whose wave) can engulf you (p. 25).

In other words, the Ethiopian Prime Minister discreetly instructed General Taddesse Birru to drastically curb the literacy campaign among the Oromo. From this, it follows that the Ethiopian government of the time feared that if the vast Oromo population had access to modern education, they would endanger the Amhara elites’ hold on power. That was why as early as 1942, Afaan Oromo, the Oromo language, was banned from use in preaching, teaching, broadcasting, and publishing. In fact, after 1942, the production of “Oromo literature was not only banned, but most of what was already available was collected and destroyed.”3 This means Haile Selassie’s regime not only banned the use of the Oromo language but also curbed literacy among the Oromo, even in the Amharic language. In other words, Emperor Haile Selassie’s regime followed a secret policy of keeping the Oromo in the darkness of ignorance.

General Taddesse Birru could not believe what he heard from the mouth of the Ethiopian Prime Minister himself. The general was shocked and awakened by the policy designed to perpetuate ignorance among the Oromo! It was the realization of blatantly discriminatory government policy that inspired General Taddesse Birru to join the Matcha-Tulama Association on June 23, 1964. That was the turning point in the life of the general and in the activities of the association.

When the Ethiopian Prime Minister got the news about Taddesse Birru joining the association, he realized that Taddesse was not an Amhara and he had mistakenly confided in him about the government’s educational policy. To ensure damage control, the Ethiopian Prime Minister targeted General Taddesse Birru for destruction. The threat on General Taddesse Birru’s life transformed the movement by forcing it to focus more on political activities rather than on its economic development program (pp. 26-27).

Ironically, the leaders of the association wanted to use General Birru’s fame, his charismatic personality, his standing within the government, and his loyalty for and closeness to the Emperor for the purpose of protecting and expanding the activities of the association. The leaders of the association did not realize that they inadvertently traded the calm activities of their organization for high-stake publicity, which intensified the fear of the Amhara ruling elites, who were eager and ready to destroy both the association and its leaders.

Here it suffices to say that after the association was legally recognized by the government, it attracted the elite of the Oromo society-civilian government officials, business and religious leaders, professionals, and military officers. By joining it, the Oromo elite elevated their status and transformed the image of and the perception about the Matcha-Tulama Association. Above all, the Oromo elite provided the association with their talents, skills, knowledge, organizational capabilities, and leadership qualities, and, in no time, they transformed what started as a self-help movement in the region of Shawa into a formidable pan-Oromo movement all over Oromia. It was a rapid transformation and a remarkable achievement; whose result became apparent in the restructuring of the association (p.29).

After reorganization, the policy-making Board of Directors was enlarged to 15 members. The Committee of the Association also grew from seven to thirteen including the Legal Committee, chaired by Bekele Nadhi; the Education Committee, chaired by General Taddesse Birru; the History and Information Organization Committee, chaired by Haile Mariam Gamada; the Cultural and Religious Committee, chaired by Haile Mariam Gemeda; the Committee for Provincial Branches, chaired by General Taddesse Birru; and the Advisory Committee, chaired by General Taddesse Birru. It is evident from this list that General Taddesse Birru and Haile Mariam Gamada were the key members of the association. Also, they were among the leaders targeted for destruction by the Ethiopian government.

The Year of The Association’s Activities.

Chapter Three deals with what is termed as “The Year of The Association’s Activities.” According to the author, considerable achievements were made in membership recruitment, as well as drafting and approving regulations for provincial district and local level development activities. The massive regulations were a blueprint for the establishment of a government within a government in terms of development activities (p.37). The association’s development activities were much more effective, energetic, and productive than the government’s lukewarm development activities. This immediately aroused the envy and jealously of provincial governors who traditionally pocketed public money collected in the name of development (p.41).

Contrary to the governors’ policy of enriching themselves at the public’s expense, the association followed a policy of using local funds for local development activities. For the purpose of raising funds and mobilizing the people for local activities, the association started organizing massive public gatherings, which became the main platform for political agitation as well as the launchpad for impressive development activities. The public gatherings were sponsored by the most privileged elements of the Oromo society such as Dajazmach Kebede Buzunesh, one of the most celebrated heroes of the war’ of resistance during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia (1935-41) who gave 50,000 hectares of his own land for the association’s development activities!

It was Haji Robale Ture, one of the wealthiest men in the Arsi region, who organized the Itayaa gathering in May 1966, a historic event that brought together the western and eastern Oromo, Muslims, and Christians to open a new era of Oromo unity. In his speech to the thousands who were gathered at Itayaa, Haji Robale Ture stressed that as “Streams join together to form a river, people also join together to be a nation, to become a country” (p. 51). Haji Robale was clearly saying let us strengthen our unity and create our country. This was a quantum leap from the original goal of self-help activities in one province to the creation of an Oromo country. Haji Robale represents only the view of a radical minority within the association.

The overwhelming majority of the members of the association, including General Taddesse Birru, did not question the territorial integrity of Ethiopia. What they questioned was the identity of Ethiopia that excluded the Oromo group. They questioned the image of Ethiopia built upon the supremacy of a single national group. They identified political, economic, and cultural inequality as the enemy of Ethiopia. Thus, their view of Ethiopian nationalism was opposed to the supremacy of one ethnic group and was based on the equality of all the peoples of Ethiopia. What radicalized the association more than anything else was the realization that the government of Emperor Haile Selassie planned to destroy the association. The leaders of the association wanted to ignite the fire of Oromo nationalism that would outlive the destruction of the association and its leaders. It was stated at the politically charged Itayaa gathering:

…that the Association spelled out its political objective which cemented Oromo unity and shattered all myths and lies about Oromo disunity. At that gathering…. the thousands of participants declared with one voice that all Oromo are one and will remain one people forever and that the artificial division that was created by the enemy is dead and buried. Among other things, at the ltayaa meeting it was noted that: (1) less than one percent of Oromo school-age children ever get the opportunity to go to school; (2) less than one percent of the Oromo population get adequate medical services; (3) less than fifty percent of the Oromo population own land; (4) a very small percentage of the Oromo population have access to [modern] communication services. [And yet they], paid more than eighty percent of the taxes for education, health, and communication.4

At the Itayaa gathering, the leaders of the association not only articulated Oromo grievances but also emphasized the importance of unity. Those who were at that meeting declared with one voice never to be divided again. From this perspective, the Itayaa gathering was the beginning of coordinated and united Oromo activities, under a single leadership (pp. 52, 167, 241), heralding the birth of Oromo nationalism.

Those who were at that meeting even overcame religious prejudice and cultural taboos. Thus, the Muslims ate meat slaughtered by Christians and the Christians did likewise. This was an unprecedented event in Ethiopia that shocked and outraged the Amhara ruling elites who branded the association a “pagan” movement (p. 172). The Itayaa meeting was addressed in Afaan Oromo, the language proscribed for public use in Ethiopia.5

In short, the leaders of the association not only overcame religious and cultural taboos, (a remarkable achievement by itself) which strengthened Oromo unity, but also challenged the authority of the Ethiopian state with regard to the use of the Oromo language in public. It was out of this challenge that the political objective of producing literature in the Oromo language was born. It was also out of this challenge that the idea of correcting the distorted image of Oromo history was born (see below).

The Itayaa meeting was followed by several others, including a meeting held in Bishofutu (Debra Zeit) in June 1966. That meeting was organized by Lemma Guya (air force captain) who was immediately transferred from Bishoftu to Asmara and then imprisoned (p. 59).

In 1966, the association formed branch offices in Arsi and several places in the Shawa province. The most important branch offices were formed in June 1966 both in the Wallaga and Hararghie provinces. It was Mrs. Astede Habte Mariam, the only woman in the highest policy-making Board of the association, who played a crucial role in the formation of the Wallaga branch office. She was a member of the Oromo royal family of Nekamete and the sister of the Governor of Wallaga. On the day when the Wallaga branch office was formed, Colonel Alemu Qietessa, the president, General Taddesse Birru, General Jagma Kello, General Dawit Abdi, Dajazmach Kebede Buzunesh, Dazamach Fiqere Selassie Habte Mariam (the governor of Wallaga), his sister, Princess Mahestena Habte Mariam (the wife of one of the deceased sons of Emperor Haile Selassie), Haile Mariam Gamada and many government officials were present.

In short, the Wallaga branch office, chaired by Mrs. Astede Habte Mariam, included not only top provincial officials but also a member of Haile Selassie’s royal family. Others, such as Major General Waqjira Serda, Fitwarari Haile Michael Zewde Gobena (the great-grandson of Ras Gobana) joined the association.

Through these top government officials, the association penetrated Emperor Haile Selassie’s bureaucracy. These individuals were privileged members of the Oromo elite. Probably, they had much more in common with the Amhara ruling elites, into which they were assimilated, than with the ordinary Oromo, who were the victims of the Ethiopian system. By joining the association, they exposed the Achilles heel of the Ethiopian system—the policy of Amharization did not consider the assimilated individuals as equals with the Amhara elites.6 There was a cultural stigma attached to the assimilated because of their origin. This predicament hastened the politicization of the culturally Amharized and the most privileged elements of the Oromo society.

This prompted civilian officials and military officers to reassess their standing within the Ethiopian political establishment and to realize the importance of strengthening a pan-Oromo movement. For years they had thought of themselves as part of the Ethiopian system and sustained an illusion of equality in relation to the Amhara ruling elite. Now, for the first time, the Christianized and Amharized Oromo elite turned its energy towards asserting its equality and that of the Oromo people within the Ethiopian political landscape.

When the educated professionals find themselves unable to gain admission to posts commensurate with their degrees and talents; they tend to turn away also from the metropolitan culture of the dominant ethnic group and return to their ‘own’ culture, the culture of the once despised subject ethnic group. Exclusion breeds failed assimilation, and reawakens an ethnic consciousness among the professional elites, at exactly the moment when the intellectuals are beginning to explore the historic roots of the community. 7

Besides the establishment of a branch office in Wallaga, the other major achievement of the association in 1966 was the establishment of a branch office in Hararghie. It was Qanzmach Abdul Aziz Mohammed, a prominent member of the Ethiopian parliament, who played a crucial role in the establishment of the Hararghie branch, which was chaired by Major General Abeba Gamada, the Commander of the Third Division stationed in the city of Harar. The secretary of this branch was Colonel Hailu Regassa. Major Teka Tullu and Captain Debela Dinsa (Dhinsa) were among many members of Hararghie’s branch office. Interestingly, the author failed to emphasize the following facts. First, Major General Abeba Gamada was among Haile Selassie’s top officials who were massacred by the military regime in December 1974. Colonel Hailu Regassa and General Taddesse Birru were executed by the same regime in 1975. Also, Qanzmach Abdul Aziz Mohammed was executed by the same regime. Ironically, Teka Tullu and Debela Dhinsa were prominent members of the military regime that decimated so many members of the association. Let us continue with the rest of the history of the association.

In fact, before the end of 1986, the association had already established branch offices throughout Oromia and beyond. It was Tesfaye Digaga who established the association’s branch office in Sidamo province. Abba Biya Abba Jobir and Dr. Moga Firissa established the Jimma branch office. Abera Yemer established the Wallo branch office. Shaykh Hussein Sura and Haji Adam Sado established the Bale branch office. Dr. Jamal Abdul Qadir and others established the branch office in the IlIu Babor province. In July 1966, Zewga Bojia and his brothers organized a large gathering in the district of Jebat and Matcha. Like so many other members of the association, Zewga Bojia was also executed by the military regime.

Maturity of the Leaders of the Association

Chapter four, which reflects the political maturity of the leaders of the association, deals with the efforts to unite the oppressed nationalities of Ethiopia against their common oppressors. Hence national oppression became the tie that bound together with the oppressed peoples of southern Ethiopia (p.75). The Matcha-Tulama Association provided an organizational framework, not only to unite the oppressed nationalities but also to end national oppression in Ethiopia.

Consequently, membership within the association was open to all. This was both a strength and a weakness of the association. It was a strength because the association became the first organization to unite the oppressed nationalities of southern Ethiopia, who, like the Oromo, were subjected to economic exploitation, political oppression, and cultural domination.

It was a weakness because open membership provided a Trojan horse for the security agents of Haile Selassie’s regime to infiltrate the association and to expose it to destruction (see below). Many Oromo and non-Oromo members of the Ethiopian Parliament were active members of the association. They were instrumental in establishing parliamentary caucuses and in popularizing the association. In other words, the leaders of the association recruited members from the Ethiopian bureaucracy, the parliament, the military, the police force, the university, and the media. They also recruited members from among the oppressed nationalities of southern Ethiopia.

Among the non-Oromo members of the Ethiopian Parliament, the following individuals were active members of the association. These were: (1) Mamo Komecha, the representative of the Gedewo people; (2) Fitwarari Abayenh Fano, the representative of the Gamo people; (3) Mulu Meja, the representative of Waleyeta people; (4) Wolde Amanuel Dubale, the representative of the Sidama people; (5) Fitwarari Ketta, the representative of the Gamo people; (6) Grazmach Bogale Walalu, a member of the upper House of the Parliament (i.e., Senate); (7) Qanzmach Gebre Oddo, the representative of the Gimira people; (8) Qanzmach Eretarn Erecha, the representative of the Gamo district people; (9) Balambaras Basha Gudo, the representative of Kulo Konta people; (10) Kebede Borena, the representative of Haiqoch and Butajira people; (11) Obsee Bargo, from Gedewso; (12) Qanzmach Haile Donomor, from Mocha; and (13) Dajazmach Abdurahman Ojallo, from Bella Shangul. Many individuals from Adare, Afar and Issa, actively participated in the association (pp. 75-77).

In short, there were 26 non- Oromo individuals who held responsible positions within the various committees of the association. This demonstrates that the association had broad support among and trust of the elites of the oppressed nationalities of Southern Ethiopia which it mobilized against collective national oppression.

The association attracted not only the members of the parliament, high ranking military and civilian officials, and wealthy traditional leaders, but also Haile Selassie I University students. They included Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir, Barto Tumsa, Ibssa Gutarna, Yohannes Leta, Mekonnen Galan and many others. Except for Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir, who was martyred in 1968 (see below), the rest were the founding members of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in early 1974. Many university students who were members of the association are not mentioned in the book, including Taha Ali Abdi, a founding member of the Oromo Liberation Front. This means the OLF leaders were the product of the Matcha-Tulama Association itself (see below).

“The Heat”

Chapter five, titled “The Heat,” depicts governmental power used to destroy the association. In late 1966, the government passed new laws that undermined the association’s activities and were used as a legal cover for the destruction of the association. The association planned to organize a mass meeting on October 15, 1966, in the town of Dheera in the Arsi province.

Dajazmach Sahelu Dufayee, who was alarmed by the rapid spread of the association’s activities, ordered the organizers not to hold the meeting. The organizers, led by the militant nationalist Haji Robale Ture, defied the order although they were immediately detained. Their imprisonment galvanized the people, and what was supposed to be a meeting for discussion about development activity was transformed into a challenge against government policy toward the Oromo.

The meeting attracted tens of thousands of Oromo peasants. It also attracted the leaders of the association from Addis Abeba, including General Taddesse Biruu, General Dawit Abdi, Dazamach Kebede Buzensh, Dr. Moga Firrisa, Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir, and many others. In his speech to the gathering, General Taddesse Birru told the people to expect nothing good from the Amhara rulers and to depend on themselves to protect and safeguard their association.

He warned them that government officials may take drastic action against the association and its leaders.8 His prophetic warning became a reality, the same day when the governor’s agents fired on those who were returning home from the meeting, killing a woman and wounding two other individuals (p.114). Many leaders of the association in Arsi were arrested. The Amhara leaders of Arsi immediately embarked on poisonous anti-Oromo propaganda, even claiming that the Oromo were “aliens” who came from Kenya, to which they have to be returned (p.114).

To those who have some knowledge of Ethiopian history, the threat of Oromo expulsion from historical Abyssinia is not new. It was attempted by both Emperors Tewodros (1855-68) and Yohannes (1872- 89). What was new in 1966 was the fact that eighty years after the Oromo were conquered and incorporated into the Ethiopian empire, they were still considered by The Amhara ruling elites as “aliens” who had to be frightened into submission by the threat of expulsion!

Such insensitivity and callous disregard for Oromo feeling and national dignity not only angered the leaders of the association but also changed their attitudes towards the Emperor who refused to heed their plea for justice. Up to this point, the leaders of the association remained loyal to the Emperor. For them, the Emperor was not part of the conspiracy to destroy the association and its leaders.

However, when the Emperor refused to stop governmental attacks on the association, the association leaders’ loyalty to the Emperor, especially that of General Taddesse Birru, melted away. For the first time, the unthinkable-the idea of physical elimination of the Emperor-started taking shape in the mind of General Taddesse Birru. The Emperor knew General Taddesse’s state of mind through his planted agents in the movement and put all the leaders of the association under constant observation by secret servicemen. It soon became obvious for the leaders that the government planned to destroy their association. Then and there, General Taddesse Birru’s major weaknesses, i.e. impatience, impulsive behavior, lack of foresight and preparation, and rashness to take action without considering its consequences.”9

Although the leaders of the association kept regular secret contact with the leaders of the armed resistance in the Oromo region of Bale, (see below) they did not plan to conduct their own armed struggle. Confronted with an imminent attack on their association, they reactively decided to rely on the men-in-uniform (who were members of the association), for attacking the Emperor and capturing state power.

In early November 1966, the threat to the life of Taddesse Birru became very clear. The life of the General and the survival of the association had to be assured either through appeal to the Emperor or through an attempt on his life. Appeal they did, but they did not prepare themselves adequately for the attack on the Emperor. Sadly, the association that focused on economic development activities and political awareness campaigns did not develop any effective military strategy. This was its major weakness (p. 296). Yet, General Taddesse Birru proceeded with his rash, unplanned, and not carefully thought-out plot to organize the assassination of the Emperor.

For that purpose, a hastily prepared meeting was held at General Taddesse’s residence on the evening of November 2, 1966. Those who participated in that fateful meeting included the host, Dajazmach Kebede Buzensh, Dajazmach Daniel Abeba (the grandson of Ras Gobana), Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir, Tesfayee Degaga, Bekle Makonnen, Dr. Moga Firissa, KetemaYefru, (the future Ethiopian Foreign Minister), and many soldiers.

It is impossible to understand why General Taddesse Birru included Ketema Yefru, the godson of the Emperor, in that plot. Either the General was too trusting, or naive, or both. Ketema Yefru, a leading member of the Amhara ruling elite, was probably a planted agent at the highest level of the association. Ketema Yefru had nothing to gain by participating in the plot to assassinate the Emperor. He had everything to gain by betraying the trust which Taddesse Birru placed in him.

Of all the individuals who participated in the meeting of November 2, only Ketema Yefru remained on best terms both with the Emperor and the Ethiopian Prime Minister. This means Ketema Yefru not only escaped punishment but also was promoted to Foreign Minister, the post he held until the end of Haile Selassie’s reign in 1974!

Be that as it may, those who met at General Taddesse Birru’s residence discussed the course of action to be taken and planned to attack the Emperor, while he was en route to St. Georgis Church in Addis Abeba. In fact, at the hastily called meeting, only one issue — the attack on the Emperor —was discussed. There was no fall-back plan if the attack failed to materialize. The Emperor was to be assassinated on November 3, 1966, on the thirty-sixth, the celebration of his coronation!

Preparation for this event lasted only a few hours, weapons were distributed, and a soldier who was to throw the first-hand grenade at the Emperor was hand-picked by General Taddesse Birru, whose goal was to seize state power in the confusion that would follow the Emperor’s assassination. In other words, Taddesse Birru aspired to replace the Emperor, declare a republic, and become its first leader. However, the plot was poorly, openly, hastily, and carelessly planned. The government’s security men not only knew what was plotted but also detained those who were returning home with weapons in their hands! The key planted agent within the top leadership of the association helped the government to easily foil the planned attack on the Emperor (pp. 122-23). The plot was a disastrous failure!

Although Dazamach Kebede Buzunsh and General Taddesse Birru rebelled, through the intervention and promise of pardon by Princess Tenagne Worq, the Emperor’s favorite daughter, and Abuna Tewoflows, the patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, they were given a temporary pardon. Dajazmach Kebede Buzunsh was the first to receive a full pardon from the Emperor, General Taddesse Birru followed suit a few days later.

In the presence of Princess Tenagne Worq, the Patriarch, Major General Asafa Demissie, the Emperor’s personal bodyguard, Dajazmach Kebede Buzunesh, and Dajazmach Kifle Ergetu, the Emperor greeted General Taddesse Birru with these words: “I pardon you for what you consciously or unconsciously did” and ordered him to return to his job (p. 132). The unsuspecting General thanked the Emperor and went home believing that he was forgiven and his plot forgotten.

General Taddesse Birru lacked the cunning and political acumen of Emperor Haile Selassie, whose regime always prepared traps for its enemies and fabricated evidence for their punishment (p. 193). On occasions, the Emperor’s security men arranged for the death of his enemy. Once the enemy was eliminated, the Emperor posthumously promoted his victim, who was then buried with great fanfare at the Trinity Church Cemetery, the burial place for great patriots and well-known dignitaries! (pp. 190-92).

General Taddesse Birru had neither the information about what was planned for him nor the farsightedness to suspect that the pardon was a ruse, a time-buying devise, intended to diffuse tension, disarm and imprison the prominent leaders of the association.

Promise and Betrayal

Chapter six deals with Byzantine imperial politics. The irony of promise and betrayal at Haile Selassie’s palace is captured in the Amharic aphorism, “Even if the sky comes down, the King’s word (promise) cannot be altered.”

Pardon was given to Taddesse Birru, but it was altered as easily as it was given. It soon became apparent that Emperor Haile Selassie pardoned General Taddesse Birru precisely because he wanted to avoid embarrassment while a meeting of the Organization of African Unity was taking place. This was followed by a state visit by the President of Czechoslovakia. Once those events were completed without incident, it was time to launch poisonous propaganda against the organization, arrest its leaders, and destroy its legal existence. The government claimed that the association planted an explosive at the Cinema Hall in Addis Abeba. The explosive was planted by government security men, one of whom lost his hand while planting it. No one was killed in the explosion although there were 654 individuals in the Cinema Hall at the time!

A few days after the explosion, Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir was arrested and blamed by the government for causing the explosion (138-48). Mamo was taken to the Cinema Hall and photographed ten days after the explosion. After he was tortured day and night, he signed a forced confession (p. 161) that became a pretext for arresting the leaders of the association General Taddesse Birru was surrounded in his house by 35 to 40 policemen and ordered to surrender. He refused and fought bravely He was not a wise politician, but he was a brave soldier. He broke out of the encirclement, killing two and wounding others (p. 153). He escaped to the rural area and rebelled for the second time. His second rebellion was as unplanned as the first one and even worse.

He was unaware that his second rebellion was doomed from the beginning. He seemed to have expected a miracle, (widespread support for his cause, which never materialized) and if no miracle occurred, he was ready to accept the ultimate sacrifice. In other words, his second rebellion was a reactive response to the government’s attempt to arrest him. He was alone. He was punished by hunger and exposed to dangerous elements. As if that were not enough, he fell into a ditch and broke his left leg. General Taddesse Birru attempted to recuperate in the house of an Oromo peasant called Abba Jifar Waqayo, who seemed to have compared the current miserable condition of the General with the power and majesty of Emperor Haile Selassie. Probably attracted by the promise of an $8,000 Ethiopian birr reward (p. 288), he betrayed the General for the cause of the Emperor. By betraying General Taddesse Birru, and taking blood money, Abba Jifar Waqayo’s name will remain in infamy in Oromo history (p.171).

Betrayed by the man who was supposed to nurse him, General Taddesse Birru was overpowered, disarmed and captured. His arrival in Addis Abeba as a prisoner closed this short chapter on his attempt to overthrow Emperor Haile Selassie. It was the saddest episode, into which he was provoked without any preparation, and those who planned his destruction and that of the association were delighted with their easy victory over what they termed “destroying the Pagan Movement in its Infancy” (p, 172).

Those who captured Taddesse Birru were immediately rewarded. Captain Gebeyhu Dube was promoted to the rank of major, and Hamsa Alaqa Mahari Maasho was promoted to the rank of lieutenant (p. 290). Those who spearheaded the arrest of the leaders and the destruction of the association were rewarded, too. Those who were rewarded include Dajazmach Kifle Eregetu, who was appointed Minister of the Interior; Major General Deresse Dubule, in charge of the Security Department; and Major General Yelema Shebeshi, who was appointed police commissioner (p. 289).

The Ethiopian Justice System

Chapters seven through ten deal with the trials of prisoners, a mockery of the Ethiopian justice system, the punishment that was inflicted on the leaders of the association, the destruction of the association and the role of Mamo Mazamir within the association. After their arrest, the association’s leaders were imprisoned in separate cells for the purpose of spreading misinformation among them, inspiring betrayal, and turning the isolated prisoners against one another; however, that strategy did not work. Despite promises of immediate release from prison, of monetary rewards, and of ambassadorial appointments, no one agreed to testify against other association leaders.

The prisoners maintained remarkable unity, despite inhuman torture, the prospect of life imprisonment and the possibility of death sentence. What spirit was it that moved them to accept incredible sufferings, long imprisonment and possible loss of life itself? Without a doubt, it was their firm commitment to the objectives for which the association was formed and their political awakening that propelled these leaders to a new historical stage of defying Ethiopian authorities even in the face of death. By so doing, they have become the symbol of courage and heroism which still motivates thousands of men and women through the hills, valleys, gorges, and forests of Oromia. Their sacrifices became their strength, a measure of their worth as leaders. The secret of Oromo nationalism made the Oromo politics of the 1960s radically different from the situation of the 1880s, when countrywide Oromo national awareness did not exist. It took eighty years for Oromo political consciousness to develop and this, more than anything else, is a testament to the crude nature of Abyssinian colonialism in Oromia.

Trial of the Prisoners.

Chapter seven deals with the trial of the prisoners. Three civilians and two military officers (Major Generals Shiferaw Tesema and Wolde Tsedeq Gebre Meskel) were hand-picked by the government to preside over the trials of the leaders of the association.

Prominent leaders of the association including General Taddesse Birru, Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir, Qanzmach Mokonnen Wasanu, Haile Mariam Gemeda, Colonel Alemu Qietessa, and General Dawit Abdi were brought to court in Addis Abeba, while the case of seven members of the association was handled in the province of Arsi (224-5).

The government brought 81 witnesses against the leaders of the association, although their fate was decided upon even before their case was brought to court. This means the court was used as a legal cover to destroy the association (pp.225, 251). In this court drama, which was intended as a public relations exercise, the government security agents were the prosecutors of the plaintiffs and the witnesses (p.256). Also, they were the torturers who mercilessly brutalized and dehumanized the imprisoned leaders of the Association. Not a single leader of the association escaped excruciating torture. Among those who were most severely tortured and crippled was Haile Mariam Gamada, accused by Emperor Haile Selassie of being the organizing genius behind the Matcha-Tulama Association (p.401). For his trial, Haile Mariam Gamada was brought to court on a stretcher!

Although he was permitted to receive medical treatment because of Prince Ras Imru’s appeal to the Emperor, Haile Mariam Gamada died within a week after being admitted to a hospital. When he was transferred from his prison cell to a hospital, Haile Mariam Gamada, said farewell to his comrades-in-arms with these words: “Neither the imprisonment and killing of the leaders nor banning the association will deter the nation’s struggle [for freedom]. What we did [ through our activities like a snake that entered a stomach. Whether it is pulled out or left there, the result is one and the same. It has spread its poison” (p. 297).

In other words, Haile Mariam Gamada told his friends that through the activities of the association they spread poison in the body politics of the Ethiopian state. The said poison was a metaphor for Oromo nationalism, which is challenging the Ethiopian state. Haile Marian Gamada went on to say “I am exhausted. I feel I am on the verge of death. I do not expect to recover. So, this is my last farewell to you. Whether we die or not, our ideas [about the freedom of the Oromo] will be realized by our children or grandchildren” (p.402). He died a few days later calmly and with confidence that he did not die in vain. In his defense, General Taddesse Birru argued that:

What makes the freedom of a people complete are many, the most fundamental of which is their equality before the law. I am denied equality before the law because of my nationality. Officers, who were imprisoned before me were paid their salary until their case was decided in court. Because of my nationality, I am treated differently. What is more, other officers were neither disgraced, nor tortured, while in police custody. Why am I disgraced and severely tortured? Spreading literacy among the Oromo, who are left behind in terms of education became my crime. I have been the victim of national oppression. I have been wrongly accused of things I did not do (pp. 257-58).

The court never considered General Taddesse Binu’s argument in its deliberation, On the contrary, the court sentenced General Taddesse Birru and Lieutenant Mamo Mazamir to death (p, 261). General Dawit Abdi received a disgraceful discharge from the military and ten years imprisonment. Colonel Alemu Qietessa faced the same fate. Others received sentences from seven to ten years of imprisonment. Even those who refused to testify against their comrades were sentenced to ten years. This was the Ethiopian justice at its best! (p. 276).

Those who were instrumental in sentencing the leaders of the association either to death or to long term imprisonment were given “gifts” of money, land or promotion. The gift was blood money for punishing the innocent and destroying a legally established association. For instance, Dajazmach Kifle Ergetu, the Minister of the Interior was given 200 gashas (200 x 40 hectares) of prime land from Gamu Gofa province and 15 gashas from Kaffa province. Major General Dresse Dubale, Minister of Security was given 30 gashas of prime land in the Awash River Valley. Wag Siyoum Wasen Haile was appointed Ethiopia’s ambassador to the Kingdom of Jordan for spying on the family members of the imprisoned leaders. One of the civilian judges who sentenced the leaders of the association, namely Agafari Schelu, (p. 289) was promoted to the rank of Fitawarari.

Although Emperor Haile Selassie changed General Taddesse’s death sentence into life imprisonment, Mamo Mazamir was hung in Addis Abeba prison in 1969, thus becoming a great martyr to the aroma cause His final words still resonate with the new generation of nationalist aroma:

I do not die in vain. My blood will water the freedom struggle of the Oromo people. I am certain that those who sentenced me to death for things I did not do, including the emperor and his officials, will receive their due punishment from the Ethiopian people. It may be delayed, but the inalienable rights of the Oromo people will be restored by the blood of their children (p. 278).

Mamo Mazamir was hung for three reasons all of which make him one of the most militant fathers of Oromo nationalism. First, Mamo produced a draft of the “History of the Oromo” which was confiscated and destroyed by the government security men. Mamo realized the degree to which Oromo history was distorted in Ethiopian historiography. It was that distortion that became one of the arsenals for disparaging Oromo culture and undermining Oromo national identity. Mamo, like Haile Mariam Gamada rejected Ethiopian historiography.

For Mamo, what is presented as Ethiopian history and taught in the school is the history of the Amhara and Tigrai ruling elites, who perpetuated the stereotype images of the Oromo. Thus, Mamo made the writing of Oromo history not only the precondition for correcting the distorted image of Oromo history, but also the ideological battleground for the Matcha-Tulama Association. In addition to this, the draft document, which Mamo prepared, included a plan for a new government, and a blueprint for a new constitution that would abolish tenancy (p. 249).

Secondly, Mamo Mazamir was an exceptionally gifted individual who had tremendous organizational skills and boundless energy. His command of both oral and written Oromo, Amharic, and English was remarkable. At the time when a number of the leaders of the association could not speak in the Oromo language, Mamo produced poems that brought tears of joy to the audience. He was an orator who attracted the Oromo youth to the movement. Most of all, Mamo was responsible for writing short plays in the Oromo language that were shown during the Matcha-Tulama Association gatherings. His short plays depicted that Oromo labor and Oromo wealth sustained the Amhara ruling elites, who imposed vicious tyranny on the oppressed people of Ethiopia.

Through his fierce oratory, poems, and short plays he moved the Oromo to tears of anger against the Ethiopian system. He made the Oromo conscious of their deprivation and the distortion of their history and urged them to be agents of their own liberation. He was the moving spirit of Oromo political consciousness that had to be crushed by the Amhara ruling elite sooner than later. His hanging represents the attempts of the Ethiopian ruling elite to suppress the Oromo political awakening.

Thirdly, and equally important, Mamo Mazamir was a highly educated and a well-read revolutionary, who was probably the only communist within the leadership of the association (p. 428). He was instrumental in establishing an organizational link between the association and the Oromo armed struggle in the region of Bale. He wrote a letter on September 10, 1965, to the leaders of the armed struggle:

The history of mankind shows that a people who rise in the struggle for freedom and independence, in defiance of death, is always victorious. The life and death struggle of the oppressed masses in the Ethiopian Empire against the hegemony of the Amhara and their allies headed by American imperialism is a sacred liberation struggle of millions of oppressed and humiliated people. That struggle will surely intensify in the course of time as the oppressed people’s organizational means and consciousness become deeply rooted. As you learnt in our discussions, the Macha and Tulama democratic movements, which was created to raise the consciousness of the Oromo people, is the present concrete situation is working day and night to put in hand coordination activities that are within our reach. In fact, the militant members are working now on the means of organizing a nationwide people’s movement which is based on realizing the aspirations of the Oromo people as a whole. Please, keep up your heroic armed struggle, defending every inch of the Oromo Nation to the last drop of your blood. The decisive war of resistance you are conducting in Bale will, despite the maneuvers of imperialism, Zionism, and local reaction, be victorious. We shall continue doing everything we can to keep in touch with you.10

This letter shows that the leaders of the association and the leaders of the armed struggle in Bale discussed how to coordinate their joint efforts. There were similar meetings and an exchange of letters up to October 1967 (p. 167). The link between the two movements intensified at the time when the association was radicalized and the armed struggle had already liberated as much as 75% of the province of Bale from the Ethiopian administration. The radicalization of the association, and the success of the armed struggle in Bale, alarmed the Amhara ruling elite “and the thought of the two in combination” became their nightmare. HangingMamo Mazamir was part of the strategy for dealing with that nightmare. Interestingly, those who witnessed Mamo’s hanging in prison included the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Aklilu Habte Wolde, who did so much to destroy General Taddesse Birru and the Matcha-Tulama Association. Other top govermnent officials who witnessed that dreadful event were the Prime Minister’s brother, Akele Woreq Habte Wolde; Dajazmach Sahelu Dufaye, the governor of Arsi; Dajazmach Kefle Eregatu, the Minister of Interior; Major General Deresse Dubale, Minister of Security; Major General Yelma Shehashi, Police Commissioner; and others. (p. 278) It is a remarkable irony of history, that these very officials who glorified over the hanging of Mamo Mazamir in 1969 were massacred in the same prison in December 1974 and buried in a mass grave! Today they belong to the dust bin of history conveniently condemned and forgotten even by what is left of the Amhara ruling elite. Mamo did not die in vain. Today he is a great hero, the ultimate symbol of courage and the source of inspiration for millions of Oromo youth. The Oromo political consciousness for which he gave his life has now become a mass movement all over Oromia.

Chapters eleven through thirteen deal with some of the major achievements of the association, the contribution of the underground Oromo movement to the Ethiopian Revolution of 1974, and what is to be done for creating a better country for the well-being of all the peoples of Ethiopia. After General Taddesse Birru was transferred to serve his life- imprisonment in Galarnso, Hararghie, he secretly contacted Oromo elders in the region and encouraged them to prepare the people for armed struggle (pp.297-98) His imprisonment in Galarnso left the Oromo of the region an invaluable legacy.Not only did it make him the rallying symbol of Oromo nationalism, but it also created a revolutionary tradition in the region The roots of this tradition were planted deep in the soil of the Chercher highlands, giving birth to the formation of the first small guerrilla army, led by the gallant Elemo Qiltu.

After the Matcha-Tulama Association was banned in 1967, some of its members fled to Somalia where they started organizing themselves against the imperial regime. Others like Ejeta Fayissa fled to the Sudan, where he formed the branch of the association (pp.298-99.) He returned to Ethiopia in 1974, after Haile Selassie’s regime was overthrown, but he was captured and imprisoned for ten years by the military regime. He died shortly after his release from prison. The militant members of the association who remained behind in Addis Abeba transformed the banned association into an underground movement, which organized members into study circles and cultural committees For political agitation the leaders of the underground movement produced literature in Afaan Oromo, English, and Amharic. Among the underground papers, The Oromos: Voice Against Tyranny and Kana Beekta played a measurable role in exposing the oppressive nature of successive Ethiopian regimes. Voice in particular aired a clear-cut political message. It called on the Oromos and other oppressed peoples to form a united front against their common oppressors. In its May 1971 issue, Voice had the following message on the question of a united front:

…. for an Oromo worthy of the name …there is one and only one way to dignity, security, liberty, and freedom. That single and sure way is to hold a common front against his oppressors and their instruments of subjugation. In this, he is ready and willing to join hands in the spirit of brotherhood, equality, and mutual respect, with oppressed nationalities and all persons and institutions of goodwill, he is equally ready and prepared to pay any sacrifice and oppose any person or groups that in any way hinder his mission for liberation from all forms of oppression and subjugation. An Oromo has no empire to build but a mission to break an imperial yoke, which makes this mission sacred and his sacrifices never too dear.11

Haile Selassie’s regime accused the leaders of the association of plotting to dismember Ethiopia. It was on the banner of “protecting the territorial integrity of Ethiopia” that the first pan-Oromo movement was destroyed and its leaders cruelly punished. However, from the book, there is nothing to indicate that the leaders of the association even distantly intended the dismembering of Ethiopia. Probably martyred heroes such as Mamo Mazamir, Haile Mariam Gamada and, later General Taddesse BiIIU, General Abeba Gamada, Colonel Hailu Regassa, Qanzmach Abdel Aziz Mohammed, Zewga Bojia, and others never entertained the idea of breaking up Ethiopia. All they struggled and died for was the restoration of the inalienable rights of the Oromo people.

The issue was persistently confused by the Amhara ruling class which looks upon any genuine struggle for the inalienable rights and equality of peoples as a dagger aimed at its privileges. Indeed, this is true If there was equality among all the peoples of Ethiopia, there would be no room for the colonial caste that now dominates the political, cultural, and social scene in Ethiopia. Behind the banner of defending and protecting the “territorial integrity” of Ethiopia, the Amhara ruling class has not only continued to confuse the real issue in Ethiopia but has managed to internationalize the issue of its own survival and privileges.”12

Among the members of the Matcha-Tnlama underground movement, the brothers Rev. Gudina Tumsa and Barro Tumsa played a remarkable role in keeping alive the spirit of resistance (pp.. 300-301). They both gave their lives for the Oromo cause. In fact, Barro Tumsa was not only the moving spirit of the underground movement but he was also instrumental in the formation of the Oromo Liberation Front in early 1974. Under his leadership, the underground movement contributed to the overthrow of Haile Selassie’s regime in 1974 in four major ways. First, its members effectively used the media, thus exposing the tyranny of the Haile Selassie regime. Secondly, its parliamentary members in the Ethiopian parliament regularly challenged many of the regime’s policies. Thirdly, its members conducted agitation among the university and high school students. Fourthly, and most importantly, the underground members of the military and police forces played a role in the formation of the military junta that overthrew the Emperor in September 1974 (pp.301-302). According to Olana Zoga, the main achievements of the association follow: (1) it created political awareness among the Oromo; (2) it united the Oromo across regional and religious divides; (3) it undermined the importance of the crown, the symbol of Amhara ethnic supremacy; (4) it exposed the Amhara ruling elite’s policy of ..divide and destroy’; (5) it demonstrated that Oromo traitors have always worked against the fundamental interests of their people; (6) and (7) it established a clear connection between the Oromo struggle for freedom and the struggle for democracy in Ethiopia (pp. 315-316, 320-321).

One interesting point discussed in the book is the grotesque distortion of Oromo history in Ethiopian historiography. The author mentions a number of writers, both Ethiopians and foreigners, who are guilty of making the Oromo people without history. In particular, the author singles out Tesfaye Makonnen for disfiguring and distorting Oromo history (p. 335). The author also indicted Harold Marcus on four grounds. First, according to the author, Marcus writes about events and personalities that are known without making any fresh and original contribution to Ethiopian history. Second, for Marcus, Ethiopian history is the history of the Abyssinian kings, thus making most of the peoples of the country without a history. Third, Marcus’ view of Ethiopian history is colored by his own political prejudice against the Oromo. Finally, according to the author, Marcus points an accusing finger at the Oromo for what happened in Ethiopia in 1991/1992 (pp. 361, 367). The author goes on to say that the present Ethiopian generation must be free from not only historical distortion, which adds fuel to the fire of conflict, but also from the political ideology that promotes the hegemony of the Amhara or Tigrai elites and the superiority of the Amhara language and culture (p. 322).

In the final chapter, the author discusses the individual history of 22 leaders of the Matcha-Tulama Association, of which only the history of Colonel Alemu Qietessa, Haile Mariam Gamada, and General Taddesse Birru will be summarized below.

Colonel Alemu Qitessa, a founding member and still president of the Matcha-Tulama Association, was born in 1914 in Jeldu Shawa province He joined the imperial bodyguard in 1934 and fought against the invading Italian force in 1935. Then he joined the resistance force and after Emperor Haile Selassie was restored to power in 1941, he received modern military training and served in the military establishment for many years. He is a man who endured pain and sorrow in the Oromo national struggle for freedom (pp. 387-92). He is a gifted orator, an able leader, and a man with wide experience.

This remarkable leader is the symbol and the spirit of Oromo nationalism. He, himself, is the living [history]. His knowledge of the Oromo language, the power and beauty of his words, the depth of his ideas, the clarity of his thought and the logic of his argument, all make him a remarkable historian who is a living hero, the legend in his own time. He has a particular way of using words, interspersed with proverbs. He can make you laugh and feel proud one moment and cry and feel sad the next.13

Haile Mariam Gamada was born to a peasant Oromo family in Jedda Wereda (subdistrict), Shawa province, in 1915. He was a secondary school student when the Italian fascist forces invaded Ethiopia in 1935. He joined the resistance force under the leadership of Ras Abeba Aregay, the grandson of Ras Gobana. He was captured as a prisoner of war by the Italians, then exiled and imprisoned in Somalia for three years. After Ethiopia was “liberated” in 1941, he returned to the country and worked in the Ministry of Labor in Shawa, Tigrai, Hararghie, Kaffa, IIIu Babor, Bale, Arsi and Sidamo.

He traveled extensively all over the Oromo country and gathered information on Oromo history, traditions, customs, and political organizations. He was an intelligent observer, a keen learner, and an avid reader, all of which made him a leading authority on Oromo history. Later on, he also received legal training at the Haile Selassie University. He made selfless efforts to free the Oromo from national oppression (pp. 398-402).

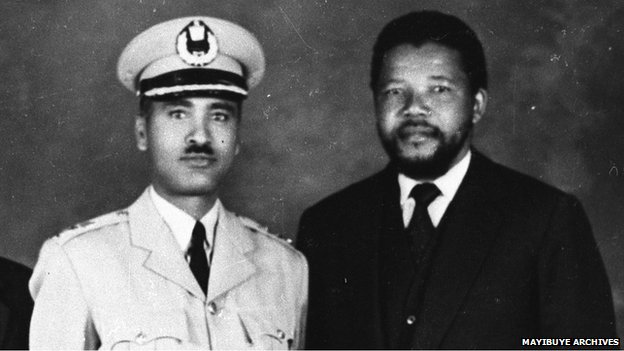

General Taddesse Birru was born into a deeply religious family in Salale, Shawa province. As a young man, he received an Orthodox church education. His father, Birru, was killed by poison gas while fighting against the invading Italian forces in 1935. His mother died within three months after the death of her husband. Tadesse joined his uncle, Balambaras Beka, who was one of the resistance leaders in Shawa province. He was captured as a prisoner of war, exiled to Somalia, and sentenced to life imprisonment in Mogadishu. When Mogadishu fell under British control in 1940, Taddesse was freed and recruited into the British force. He was given military training in Mombasa, Kenya, and returned to Ethiopia to fight against the Italian forces He was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant in 1942 and served in Hararghie province. Later on, he received advanced military training at the Haile Sellassie military training school in Holota, where he served as an instructor. By 1955, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and transferred from the military to the police force. He established Rapid Force, the elite riot battalion. He earned fame and respect for his mastery of military science. He trained many of the best Ethiopian officers. Emperor Haile Selassie entrusted to him the training of a number of leaders of liberation movements in Africa, including Nelson Mandela of South Africa. In his recently published book, President Nelson Mandela acknowledges Taddessee Birru as the man under whose guidance he received his first military training in the early 196Os. In his own words,

I was lectured on military science by Colonel Tadesse who was also Assistant Commissioner of police. In my study sessions, Colonel Tadesse discussed matters such as how to create a guerrilla force, how to command an army, and how to enforce discipline.14

After his return to South Africa, Nelson Mandela created Umkhonto we Sizwe, the spear of the nation, a new liberation army on the basis of “the art and science of soldiering”15 which he received under Colonel Taddesse Birru. It is the irony of history that Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1963 by the Apartheid Regime of South Africa, while Taddesse Birru, too, was sentenced to life imprisonment by the regime of Emperor Haile Selassie. While Nelson Mandela lived to see his release from prison after twenty-seven years, to become the first democratically elected Black President of South Africa, Taddesse Binu, who struggled for the freedom and equality of the Oromo was executed without any due process of law and buried in a mass grave!

This, more than anything else, reflects the sad reality of the Oromo situation in Ethiopia, and the impunity with which their leaders are decimated! In this respect since the colonization of Oromia in the 1880s, from the time of Emperor Yohannes IV (1872-89) up to the times of Meles Zenawi (now,) Ethiopia has failed to produce a single government that did not destroy Oromo organizations, a single government that did not kill Oromo leaders, a single government that did not plunder Oromo property, a single government that did not abuse the human and democratic rights of the Oromo, a single government that did not slaughter innocent Oromo, a single government that did not divide the Oromo and turn them against each other, a single government that did not attempt to destroy the Oromo identity, a single government that respected Oromo national dignity, a single government that did not destroy Oromo institutions, and above all a single government that did not monopolize political and military power for the purpose of perpetuating colonial status quo in Oromia!

This means that in Ethiopia governments have changed, leaders have changed. But the economic exploitation, political domination, and military subjugation of the Oromo, or the colonial status-quo of Oromia, remain constant. To end colonialism and create a free and independent Oromia are the ultimate goals of Oromo nationalism. Although it has not yet achieved its ultimate goals, the Oromo nationalism which the Matcha-Tulama Association created “has fundamentally altered the Oromo perception of themselves and how they are perceived by others.”16

Today the Oromo are free in their mind, soul, and spirit. Those who torment the Oromo must realize that they will never be able to kill the spirit of freedom, the love, and yearning for self-determination that now reside in the Oromo nation. “Because of their numbers, geographical position and rich natural resources of Oromia, the Oromo are destined to play an important role in the future of the Horn of Africa. Consequently, Ethiopians should make an earnest effort to understand the reasons for and come to terms with the Oromo quest for self-determination.17

Editor’s Note: This article was republished from the Journal of Oromo Studies, Volume 4, 1997.