“Hachalu had a wonderful personality”-An interview with Guyo Wariyo

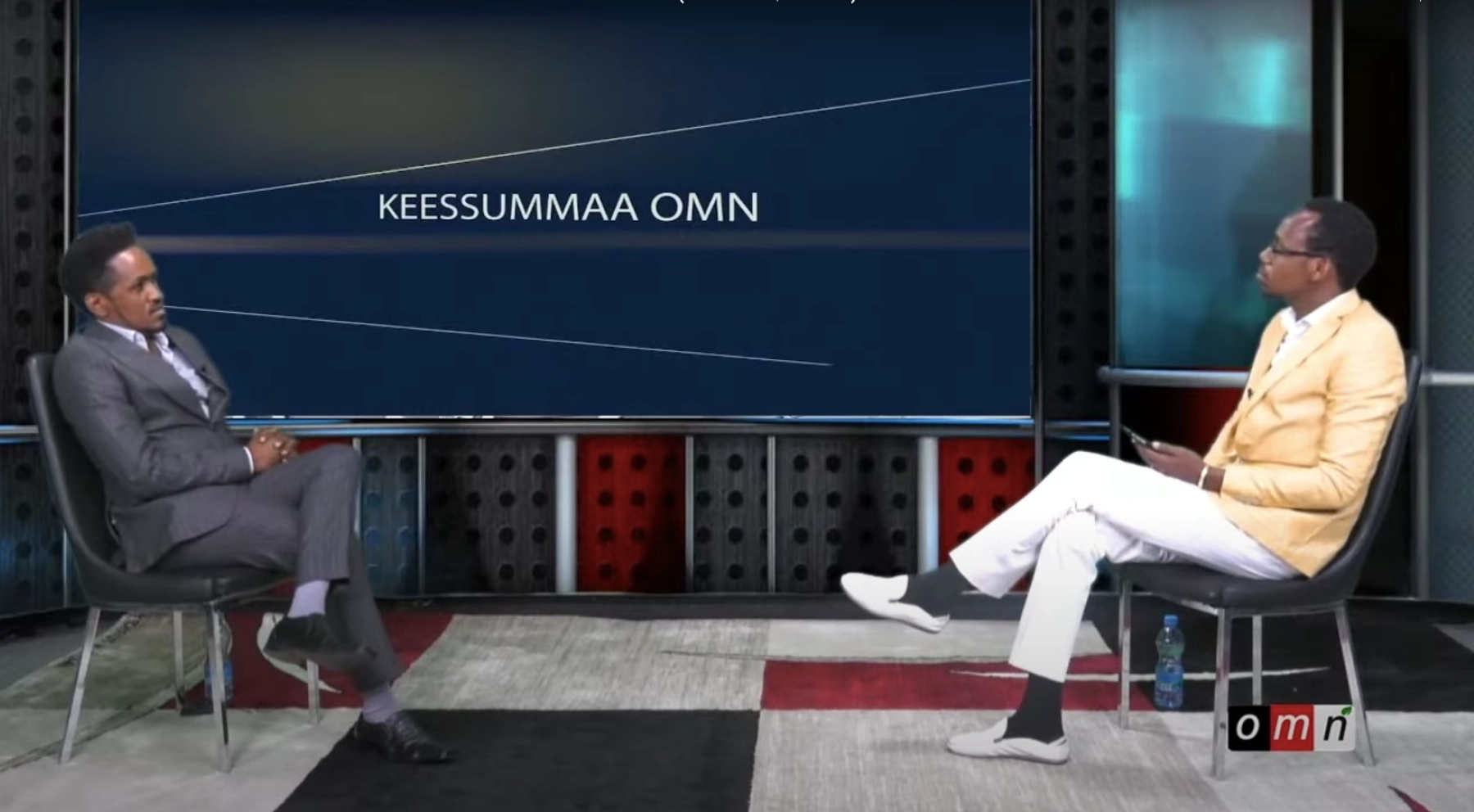

Screenshot of Hachalu Hundessa’s interview on OMN (Oromia Media Network), June 22, 2020.

You are one of the few journalists whose popularity skyrocketed in the brief time that Ethiopia enjoyed a semblance of press freedom, but we would like to know you personally. Would you like to introduce yourself to Curate Oromia and its readers?

Thank you. My name is Guyo Wariyo AbbaJirma. I was born and grew up in Negele Borana, Guji Zone of Oromia. I studied there until grade twelve and then joined Mekele University where I graduated with a degree in Journalism and Communication. I also hold a master’s degree in Journalism from Addis Abeba University. So far in my career, I have worked in different capacities for institutions such as the BBC and Oromia Broadcasting Network (OBN) and, of course, OMN. For OBN, I only worked for forty-two days, after which I was fired, but we can come back to that later.

How did you pick up an interest in journalism? Did you always want to be one?

Absolutely. I knew I wanted to be a journalist when I was seven. I really loved listening to Sora Halake on VOA Afaan Oromoo. He was my inspiration. And Qabale Jirma, a Kenyan-Oromo journalist at the Afaan Oromo service of Kenyan Television Network (KTN). She was very popular and one of the journalists I looked up to.

I remember I used to go around our neighborhood and interview people randomly. I was known as a journalist even at that age. So, in University, I already knew that I was going to pursue journalism.

How did you find the Ethiopian Media landscape starting up as a journalist?

The Media in Ethiopia is mainly government-owned and it’s difficult to even consider them as media; they are just propaganda machines. That is why my time at OBN lasted for forty-two days only. They come and tell you to do a story that is completely false. So, I hoped that I would one day work for an independent media that serves the interests of the masses, and that independence I only got at the BBC and OMN.

Let’s talk about OMN. How freely did you as a journalist and OMN as an institution work in the early stages of the “reform”?

In the beginning, there was some freedom. Personally, I took over Keessuummaa, an old program on OMN the content of which was slightly different from what I had in mind. Since I was interested in politics, I decided to turn it into a platform where I would invite public and political figures and challenge them. Our country, as you know, has been under repression for years; all of our governments have been dictators by their character. So, this, I thought, was the perfect time to challenge them, to show these influential people the power of journalism.

I started out with Obbo Junedin Sado, the former president of Oromia. I then proceeded to interview the likes of Abba Dula Gemeda, Merera Gudina, Bekele Gerba, Taye Dendea, Mamo Geda, etc. In no time, Keessuummaa became a huge success, so much so that I started to get calls from government officials and the opposition asking me to come on the program to be interviewed. Everybody loved it.

Other programs on OMN did also a great job of challenging the government, criticizing them, and raising public awareness. The Ethiopian Broadcasting Authority (EBA) would sometimes send us warning letters, but nevertheless, we worked freely until the day our office was shutdown.

Did you see that coming?

There were signs. Some months into the reform, the cadres and officials at the wereda level, who not long ago were happy to cooperate with us, started to get angry whenever we call them to investigate conflicts or when we call them to simply ask for information. They suddenly became very rude. “you are calling from OMN, we are not going to talk to you”, they would say. From then on, things just got increasingly difficult and I felt the media space narrowing right in front of our eyes.

Let’s come to Hachalu. He was your friend. How close were you to him?

The first time I met Hachalu was at the BBC Media Action office in Finfinne when he came to visit his music producer, Amensisa Ifa, who was also our sound technician. When he saw me there, he said “oh, you are from Borana! You and I are going to become very good friends.” He was very funny and innocent. He loved singing. He would sing everywhere, even when he was driving. He loved talking to people. He was also a very good storyteller. Hachalu had a wonderful personality.

Later when I joined OMN, he would always ask to be interviewed by me whenever OMN was doing a story on him. He was attacked on the streets of Finfinne if you remember, and he personally asked to be interviewed by me about that incident. He really was a close friend of mine.

Did he talk to you about those attacks personally?

He used to receive a lot of threats in Finfinne. He had been attacked more than five times. He told me that when the youth see him driving around the city, they would insult him, call him ‘zeregna’ (racist), ‘extremist’, and the like. He had told me about these things a lot of times. He has spoken about it to the media. Even the government knew about this.

How did the interview come about?

The idea of having this interview started in February. I met Hachalu at Elili Hotel by accident, and he told me that a lot of people are criticizing him saying he has betrayed their cause, that he has received money from the government, and that he wants to come onto the show and clear his name. I agreed and went ahead and posted this on Facebook on whether or not people have any questions they want to ask him. A lot of people commented.

The interview, however, didn’t materialize as he got busy and it would be two months before he reached out to arrange the interview. By then, Covid -19 had complicated our working process at OMN and we had to postpone the interview once again. Some two months after that, I was sitting at home when I received a call from him.

We met at Eilili Hotel, discussed, and set the date for the interview. I called once more to ask him about how he is going to be dressed up. He said he will wear this suit that was given to him as a gift by somebody from London. I told him that I would have to go to the laundry as none of my suits were clean at that moment. He said don’t bother! So, you remember the yellow coat I had on while interviewing him? That was Hachalu’s gift to me.

Click here to read part two of this interview.

We need your support

We trust you found something of value in this article. If so, we kindly ask you to consider helping Curate Oromia continue its work.

If you believe in the importance of independent voices and honest reporting, we invite you to support our efforts through our GoFundMe campaign.

Every contribution, however small, goes directly to our writers and the expansion of our reach.

Thank you for your support.