Under the flowers of the Olive tree, I see the leaves of the Odaa tree.

They are, of course, from different lands, separated by seas and histories. Their trunks bear branches scarred with massacres, leaves wilted from the harshness of violence. They stand as testament to the decades-long suffering inflicted underneath their shade, their grounds soaked with generations of indigenous blood. They are the roots we share.

To be Oromo is to understand suffering. My first exposure to state violence came October 2, 2016, when hundreds of Oromos would be martyred at the hands of governmental forces while celebrating Irreechaa. A peaceful holiday observing ancient Oromo traditions, disrupted by the violence of a state built upon the destructive legacy of an old Ethiopian kingdom.

The massacre was a confrontation months in the making, a culmination of Qeerroo – young Oromo activists – protests, boycotts, and unrest forcing the autocratic government to contend with the popular dissent of its constituents.

I vividly remember my mother’s face the moment she received the news: how her eyes mourned for her people while her heart feared for family members who may have fallen victim. In the days that followed, I would attend my first Oromo protest and begin to comprehend what it truly meant to be Oromo. The development of my political consciousness came not through a gradual understanding of the world, but rather an abrupt reckoning where the martyring of my people shattered any naive perceptions as I confronted the boundary between what I knew and the sobering truth.

I soon realized that the history of our struggle was carved into the very roots of our identity, weaved into the tapestry of our culture. I may not fully speak my mother tongue, but every song I danced to as a child was crafted with drums of resistance and stories of struggle.

The geerarsas – traditional oral poetry – of Haacaaluu Hundeessa and Ebbisa Addunya were history books narrating the Oromo experience from the birth of Borana and Barentu to the Qeerroo uprising. The Odaa tree nestled into our callee, sewn on our clothes, and ingrained in our flag acts as both a symbol of Oromo indigeneity and generational resistance.

Even the Amhara names of my mother, aunt, and countless family members is enduring proof of a time where Oromo parents had to choose between maintaining traditional Oromo naming at the expense of public berating and discrimination, or assimilating their children into the homogenous Habesha culture which dominated mainstream Ethiopian society.

Eenyummaan keenya qabsoo keenya dha. Our identity is our struggle. Every aspect of our culture is built upon ancient traditions and generational sacrifices to maintain those roots. For Oromos, the personal has always been political, for the individual choices each person makes arises out of the larger social and political structures we find ourselves in. For me, the Oromo struggle became the framework for all my organizing.

The Irreechaa massacre began a years-long dive into Oromo history. The systematic utilization of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church as a political tool to advance the expansion of the Abyssinian Kingdom. The banning of Afaan Oromo in official settings under the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie. The premeditated murder of political singer Ebbisa Addunya. Each of these events are a separate vein of the same leaf of violence, oppression, and subjugation which are no stranger to the Palestinian people. They are the struggles our branches burden.

To be Oromo is to have unwavering solidarity with all oppressed people. My devotion to Palestinian liberation stems from my own understanding of oppression. In Palestine, I see the similar ways cultural resistance is utilized to preserve indigenous identity as it is in Oromia. I learn of the various forms of oppression inflicted upon the population which I am all too familiar with in Oromo history. I do not conflate any two struggles to be identical, but rather frame them as mechanisms which work similarly even if the hands of power appear different.

That is not to say there are no tangible connections between the two powers. Israel has a history of providing aid to the Ethiopian empire and state in the latter’s efforts to quell resistance and cries of injustice. It materializes as the substantial military aid sent to Ethiopia when fighting Eritrean secessionists, and the training of special units to be deployed across the country.

For the Oromo struggle, the 1960s Bale insurgency—with Oromo farmers revolting against the feudal system—was crushed with assistance from Israel, where, in the words of an Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) newsletter, “eight years of guerilla struggle in Bale needed the aid of Israeli explosive experts” to be ended.

Even in the wake of the 1948 Nakba–as Israel displaced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians off their land–the Israeli state was involved with various other governments persecuting indigenous peoples worldwide. Interconnected systems means that one will always be upheld by the other, chains of oppression woven together by authoritarian hands.

I will never be able to comprehend the sheer totality of suffering which Palestinians have endured and continue to endure. Yet my personal experiences allow me to meaningfully empathize to a degree which prompts action. Although I cannot understand the overwhelming grief of 100+ family members being killed, the unlawful murder of my grandfather and great uncle urges me to march in the streets calling for an end to senseless slaughter.

Despite not being personally affected by the Israeli state’s systematic imprisonment of Palestinians, the unlawful detention and beating of Oromos pushes me to speak out against governments which shake their fist of incarceration in the face of criticism and popular dissent. In each instance, my solidarity changes shapes, the personal becomes political, the “I” of my oppression becomes a “We” towards collective liberation, and I find myself extending branches of my tree to the other as our leaves reach towards the light of a new day.

To be Oromo is to believe in Bilisummaa – freedom. That despite centuries of struggle, there remains a revolutionary flame which will pass down generations until it is snuffed out by the newfound air of freedom. As a second Nakba unfolds before our eyes, I attempt to ensure that my personal cries of Oromo liberation contain the liberation of Palestine, and of every other nation and people who fall victim to the ruthless capitalist, imperialist system of the West.

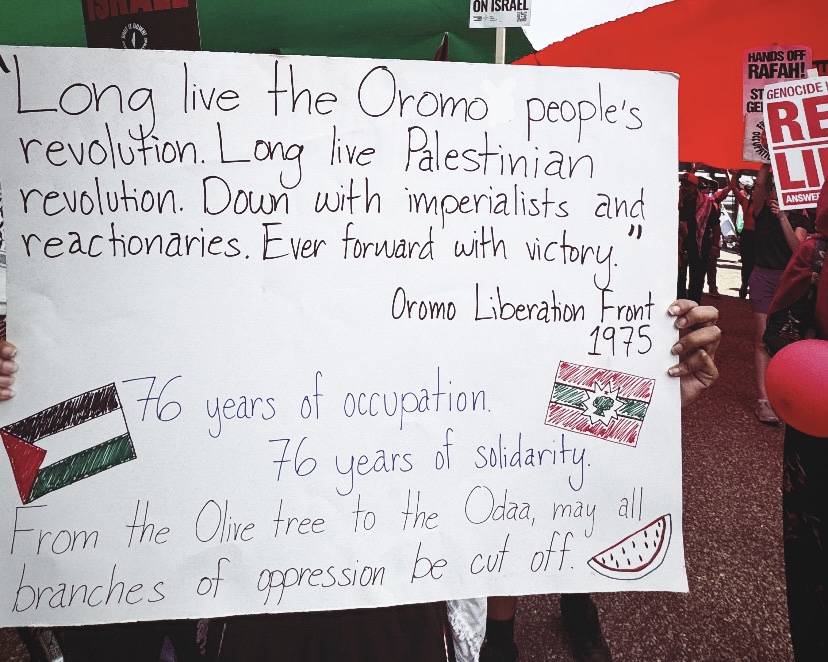

These days, I am constantly reminded of a 1975 OLF statement which reads: “Long live the Oromo people’s revolution. Long live the Palestinian revolution….Down with imperialists and reactionaries. Ever forward with victory.” 49 years later, as we reflect upon the history of the Oromo struggle and the future of our people, this solidarity continues. From the Olive tree to the Odaa, may all branches of oppression be cut from our common roots of resilience, and may we grow in solidarity and towards liberation.