The war Ethiopia cannot avoid: The opposition’s role in charting an alternative path to political transformation

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed meets with senior Ethiopian National Defense Force generals to discuss national and regional peace and security issues, Feb. 12, 2025. (Photo: ENDF)

By Muhammed H. and Idris A. 1 Muhammed H. and Idris A. are Professors at Addis Abeba University (AAU.)

Under the Prosperity Party’s rule, Ethiopia is ambling toward another war against Tigray. The Pretoria Agreement, once deemed as a path to peace, has deepened internal political divisions in Tigray, leaving the country on the brink of renewed conflict. Ethiopia’s political opposition remains fragmented, the economy continues to deteriorate, and armed resistance is growing. Prime Minister Abiy’s escalating crisis—marked by increased repression, ethnic manipulation, and military coercion—has left no room for democratic alternatives.

The reality is stark. The regime has closed off all political avenues, making coordinated resistance and strategic realignment the only viable path forward to bring about change. However, for this transition to succeed, Ethiopia’s opposition forces—including the Tigray Defense Force (TDF), Fanno, the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), which has seen none of its agreements honored, must not only work together militarily but also engage all stakeholders in dialogue to forge a post-Abiy future.

This article outlines the critical steps Ethiopia’s opposition must take to prevent the country from descending into prolonged instability, political fragmentation, and the possible emergence of competing nodes of power. The Prosperity Party regime, despite its repeated claims of invincibility, is irreparably damaged to the extent that it cannot re-establish legitimate rule. It falls to the opposition to envision a post-Abiy political dispensation and create an inclusive governance framework that can serve as a viable alternative to the tottering regime standing on the precipice of a violent collapse.

Prime Minister Abiy’s War on Tigray: Past and Future

Since coming to power, Abiy Ahmed’s tenure has been characterized by contradictions. No sooner had he won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize than he began waging a relentless and brutal war against Tigray, which was initially framed as a law enforcement action, then escalated to a security operation, and eventually morphed into an existential struggle for Ethiopia’s survival. It turned out to be a war of choice aimed at ethnic cleansing. There is evidence of intent to suggest charges of genocide are credible. Prime Minister Abiy has variously referred to Tigrayans as a “cancer,” “nocturnal beasts,” and “weeds.” Deacon Daniel, his senior advisor, openly declared that Tigrayans must be “removed from memory, public consciousness, and the annals of history.” Finland’s Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto, who visited Ethiopia in February 2021 as a European envoy, also reported that Ethiopia’s leaders told him that “they are going to wipe out the Tigrayans for 100 years [adding the intention] “looks for us like ethnic cleansing.”

The war toll has been catastrophic. Over one million civilians have died, while military intelligence sources estimate that more than 370,000 Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) soldiers have been killed, nearly 60,000 TDF fighters have perished, and up to 50,000 Eritrean troops have reportedly lost their lives. Ethiopia has suffered approximately $70 billion in economic losses, with reconstruction costs projected at an additional $20 billion.

Ethiopia’s rulers do not seem to have learned anything from the horrors of the last war. Astute observers of the Ethiopian political scene view Prime Minister Abiy’s February 3, 2025 message to Tigray, written in Tigrigna, as the opening salvo of another round of war. While it is true that the content of the message conjures memories of the road to the previous war, in which he sought to destroy as many Tigrayans as possible, it seems the current message is targeting intellectuals, business leaders, clergy, and community organizers. It seems he reckons that he can crush Tigray’s ability to resist once and for all—in the same way the Khmer Rouge sought to eliminate Cambodia’s intellectual class to prevent future opposition.

The coming war is not just about territorial control but about the systematic erasure of those who could rebuild and lead Tigray’s future.

The Pretoria Agreement: A Peace Pact or a Catalyst for Conflict?

The Pretoria Agreement, signed on November 2, 2022, was meant to end Ethiopia’s Tigray war by withdrawing foreign forces, reintegrating Tigray into national politics, rebuilding the region, and restoring its economy. On the contrary, it has worsened political instability, exposing internal divisions and providing an opportunity for Abiy to reassert control over post-war realities. The agreement has also exacerbated the leadership vacuum in Tigray, fueled tensions, and undermined any hope for a unified resistance or stable governance.

Since Meles Zenawi’s death, Tigray has lacked a capable leader who is able to rise above existing cleavages. The implementation of the Pretoria Agreement has created rival political factions and widened the rift between the Interim Administration headed by Getachew Reda and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) led by Debretsion Gebremichael. The TDF has announced that it recognizes the Debretsion faction as the legitimate TPLF group while lamenting that both sides have been willing to engage in political squabbles at a time of grave danger for Tigray. This internal division and the ensuing leadership crisis have given Abiy an opening to manipulate the region’s political dynamics and consolidate control. Ironically, Pretoria has turned out to be a vehicle for Abiy to reassert control over Tigray rather than a path to peace.

The crisis has also exacerbated competition for scarce resources. The Tigray elite, who previously held federal positions, is now confined to Tigray and forced to compete for handouts from the federal government. Prime Minister Abiy has used the agreement to divide Tigray, selectively granting resources to deepen factionalism. By demanding Tigray’s disarmament, he has exerted pressure on the TDF in order to weaken and dismantle it. With Tigray’s physical and economic infrastructures in shambles, Abiy has used financial support as a weapon to turn former allies into rivals competing for his largesse, shifting their focus from collective recovery to group survival.

On balance, Tigray’s struggle and the sacrifices it paid have yielded nothing. Forced to withdraw TDF fighters in 2021 from near Addis Ababa due to international pressure and the TPLF’s political lack of preparedness, the TDF’s efforts to defend Tigray’s interests and rights were left in vain. Western Tigray, the region’s agricultural heartland, remains occupied by ENDF-trained militias called the ‘Tekeze Guard’. Federal representatives mock Tigray’s leaders’ demand for restoration of their region as naive overtures. Even Getachew Reda, who is otherwise deferential to federal authorities, was reportedly told, “You don’t even have full control over Axum; why are you asking about Western Tigray?” This humiliation has fueled doubts about the wisdom of counting on the federal government to keep its side of the bargain in implementing the Pretoria Agreement.

Tigray’s present reality is one of forced survival, displacement, and political marginalization. Despite being a signatory to the Pretoria Agreement, the TPLF is drifting toward political oblivion. On February 13, 2025, the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) banned the TPLF from political activities for three months, undermining the Pretoria Agreement and setting the stage to outlaw the half-century-old political organization. This move highlights that Abiy is intent on systematically dismantling opposition forces. It also proves that the agreement was never intended to foster political inclusion but to neutralize Tigray’s role in national politics.

Meanwhile, an estimated 2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) are unable to return home, over 60,000 refugees are stranded in Sudan, and 40 % of its land is still under occupation. Tigray has had no political representation at the federal level for more than two years after the signing of the Pretoria Agreement. The harrowing humanitarian crisis that peaked during the war continues to deteriorate. The longer these grievances remain unaddressed, the more likely the region will be drawn back into conflict. The Pretoria Agreement, rather than resolving Ethiopia’s war, has merely reshaped it—turning visible battlefields into hidden political and economic struggles, with Tigray’s fate hanging in the balance.

Shifting Alliances: A Fractured Battlefield

As Tigray braces for another round of war, a fundamental question emerges regarding how alliances might shift in the next conflict. The previous war was defined by clear battle lines—Tigray against the Ethiopian federal government, Eritrean forces, Amhara regional forces, and the backing of all regional governments, along with Emirati financial and material support. However, the evolving political and military landscape suggests that the next confrontation will not simply mirror the past battlefield formations. Instead, it will be shaped by shifting loyalties, fractured coalitions, and a rapidly changing balance of power. Let us examine the eight (8) key forces shaping this conflict landscape.

- Eritrea’s Shifting Role

Eritrea’s deep-seated hostility toward the TPLF fueled its brutal conduct in the Tigray war. However, shifting dynamics have since altered its role. From Eritrea’s perspective, it has settled its score with its archenemy, reclaimed lost territories, and improved its diplomatic standing in the region. In fact, Asmara now considers Ethiopia a greater threat than the TPLF. In response, the TDF is recalibrating its strategy vis-à-vis Eritrea. General Tsadikan’s rejection of a proposal to deploy federal troops to the Eritrean border signals that Tigray no longer perceives an immediate threat from Asmara.

At the same time, the Tigrayan community remains deeply distrustful of the ENDF due to past atrocities. Deploying federal troops to the border would all but guarantee a war with Eritrea, forcing the TDF into a conflict and advancing Abiy’s interests of weakening both forces while advancing his ambition to regain control over Assab. This scenario paves the way for potential tactical understandings between Tigray and Eritrea, securing alternative supply routes for Tigray and undercutting Abiy’s blockade strategy.

Meanwhile, Eritrea’s distrust of Abiy has deepened, especially regarding Ethiopia’s declared desire for Red Sea access. Asmara sees Prime Minister Abiy’s Somaliland Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) as a Trojan horse for territorial claims and remains wary of Ethiopian designs on Assab Port. Isaias Afwerki’s recent remarks opposing the dissolution of the TPLF suggest a strategic shift—Eritrea may now view the TPLF as a counterweight to Abiy. More critically, the Abiy-Isaias alliance has all but collapsed, with both leaders now backing each other’s enemies. The Eritrean opposition’s recent meeting in Addis Ababa underscores their animosity, while armed Eritrean opposition activity in the Afar region further signals growing tensions.

If war reignites in Tigray, Eritrea will no longer be Abiy’s enforcer but a power broker, leveraging its northern Tigray buffer zone to dictate terms rather than follow Addis Ababa’s lead.

- The Rise and Fall of the Amhara-Abiy Alliance

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s pact with the Amhara elite, once a cornerstone of his rule, has collapsed, leaving the Amhara region in crisis. Though the pact was initially forged to weaken Tigray, the Amhara leadership had a hidden goal of securing territories such as Humera, Wolkait, and Raya. From their perspective, Abiy was merely a means to an end. Yohannes Buayalew, a former member of the Amhara regional council, captured this sentiment succinctly when he remarked, “he is a froth floating on top,” implying that the prime minister would be discarded once Tigray was subdued.

For his part, Abiy allowed Amhara forces to commit atrocity crimes in Tigray, aiming to create irreconcilable animosity between the two groups and eliminate any possibility of them forging a common front against his power. In addition, he reckoned that the Amhara forces he helped organize to obliterate the TDF would pose a dangerous threat if they remained armed. Immediately following the signing of the Pretoria Agreement, Abiy set out to abolish the regional state Special Forces. The Amhara leadership interpreted the move as a ploy to disarm Amhara forces, rendering them defenseless against the Oromo-dominated federal government. Accordingly, the Amhara forces quickly regrouped and turned their guns against the prime minister.

In effect, Pretoria silenced the guns in Tigray but ignited them in the Amhara region. The Amhara elite, who once sought to “blow the froth off,” now found themselves engaged in a mortal struggle with their former benefactor. The consequences have been catastrophic. Drone strikes and ongoing conflict with the ENDF have resulted in 15,000 civilian deaths. Of the 917 health facilities in the region, 457 have been affected by the conflict. Additionally, 1,500 schools were destroyed, 4,870 remain, and over 4.7 million children are out of school. The region that once sought territorial expansion is now a scene of displacement, famine, and insecurity.

Public support for the Fanno fighters within the Amhara region is apparently cresting due to the heavy burden imposed by the government’s crackdown. However, outside the Amhara region and in the diaspora, their support is at an all-time high. The potential entry of the TDF into the war could ease Fanno’s combat burdens, as the ENDF would be forced to redeploy troops to the Tigray front, reducing military pressure on Fanno.

Fanno’s lack of centralized command, which initially allowed them to mobilize their respective provinces and mitigate leadership losses, now makes it easier for the TDF to negotiate with the various Fanno leaders—many of whom see Abiy as the graver threat than the TDF. The decentralized command structure presents an opportunity for agility, mobility, and operational coordination, but it might prove counterproductive in the long run. The fragmentation will make negotiations increasingly difficult as each faction represents a different province of Amhara with its own priorities and leadership.

While such an approach may find domestic support, the Amhara diaspora remains skeptical of the TDF due to historical grievances. However, with effective political engagement, the TDF could gradually reshape diaspora perceptions and foster a broader strategic realignment against Abiy.

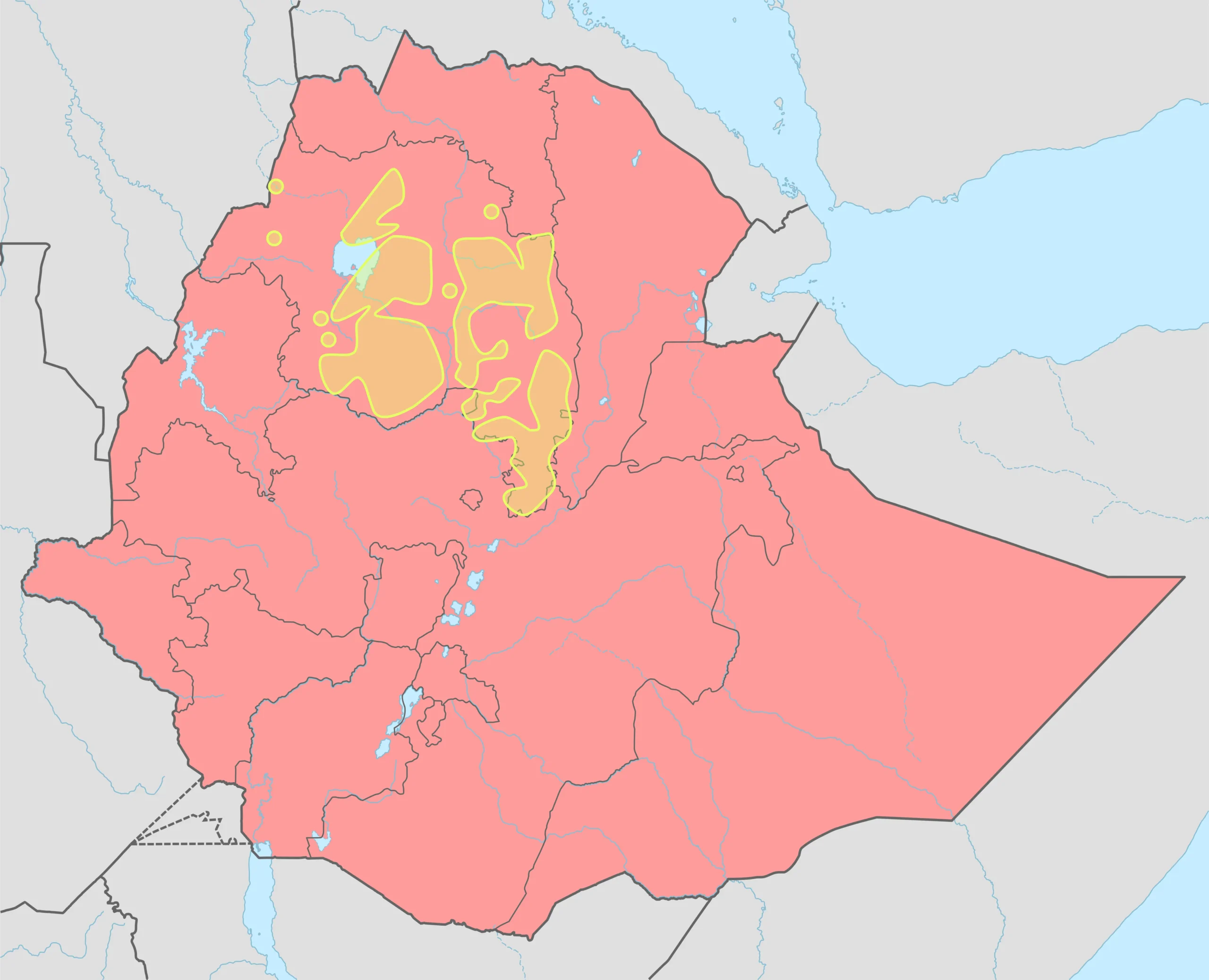

- The Erosion of Oromo Support and the Looming Threats

Once widely supported by the Oromo, Abiy Ahmed’s rule has now become an object of deep resentment in Oromia. Though he initially positioned himself as a champion of Oromo resurgence, his tenure has been marked by unprecedented violence and repression of the Oromo. Leading Oromo voices argue that the loss of lives and livelihoods the Oromo suffered under his government surpasses that which occurred during Menelik’s conquests and the subsequent imperial, military, and federal regimes combined. The region is plagued by insecurity, forced conscription, economic coercion, and rampant corruption, where even basic government services require bribes. The very people who once rallied behind him now see him as a liability.

Abiy’s strategy for consolidating power has been clear. In a speech to the now-defunct Oromo People’s Democratic Front (OPDO), he once asserted that his party must maintain total control over Oromia and use any means necessary to eliminate all opposition. His approach has divided the Oromo political elite, forcing many into subservience. The economic elite, who once supported him in hopes of expanding their businesses, have now been emasculated by the adverse effects of his policies and his constant demands for contributions to his vanity projects. Oromo intellectuals, once considered his base, are now actively distancing themselves from his regime, deeply concerned that the atrocities committed in the name of the Oromo are irreparably damaging the Oromo political cause. The level of discontent and internal fractures has become so severe that his supposed Oromo base is now shifting in ways that threaten his power.

If war breaks out with Tigray, Abiy will face an impossible dilemma. In the past, he relied on Oromia Special Forces (Liyu Police), Oromo militias, the Oromia Police, and paramilitary groups such as Gachana Sirnaa (Defender of the System) and Koree Nagenyaa (The Peace Contingent) to fight the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). These forces afforded him a free hand to deploy the entire ENDF to the north. However, with the OLA insurgency intensifying, the militias and police can no longer contain them, making his strategy of relying on Oromia forces unviable.

Redeploying troops to Tigray would leave Oromia open to the OLA insurgency, which has already rendered large parts of Oromia ungovernable. If Abiy shifts his forces, the OLA could push into major urban centers and even threaten to choke off Addis Ababa by blocking off all major roads leading to the city.

Conversely, if Abiy chooses to focus on securing Oromia, his ability to wage war on Tigray will dissipate. Unlike the situation during the last war, he can no longer recruit Oromo fighters, who would rather flee the battlefield or defect to the insurgency. According to an ENDF report, 69,000 soldiers—mainly from Oromia and Amhara—have already defected to join either OLA or Fanno or returned to their place of birth. The situation is precarious and signals a diminishing will to fight among Oromos defending Prime Minister Abiy’s rule.

Further complicating matters, the Oromo elite within the regime fear a “northern alliance” of Tigray and Amhara. Given the scale of atrocities security forces have committed under Abiy’s authorization, they fear massive reprisals in the event of the collapse of the Oromo-led government. To preempt such an outcome, there are whispers that some Oromo Prosperity Party leaders and Oromo generals are conspiring to stage a preemptive coup d’etat to ensure a larger share of power in a post-Abiy governance arrangement.

- Other Ethnic Groups?

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s rule has subjected all Ethiopians—regardless of ethnicity—to a harsh life. While some once hailed him as a liberator from the TPLF, most have come to recognize that his leadership has been the most destructive in Ethiopia’s modern history. Unlike past regimes, which had clear political structures and policies, Abiy’s governance is marked by insecurity, economic hardship, uncertainty, ad hoc governance, and corruption.

For the first time, Ethiopians across all ethnic lines share a similar experience—one of financial struggle, lawlessness, and a collapsing state. Inflation has made survival a daily battle, corruption has rendered basic services inaccessible, and violence has left communities living in fear. Those who once believed Abiy’s rule would stabilize Ethiopia now see it as the root of their suffering. Moreover, ethnic groups such as the Wolaita and Gurage, who sought regional autonomy, were denied, further fueling their grievances and deepening the sense of marginalization among their communities.

To maintain power, Abiy has weaponized the Ethiopian security apparatus against Ethiopians. In particular, he relied on the Oromia security forces as a last resort when dealing with opposition forces representing other ethnic groups. His strategy has been deliberate:

- Fuel border disputes between Oromos and neighboring regions, ensuring continuous conflict.

- Position himself as the protector of Oromos while presenting other ethnic groups as existential threats.

- Prevent Oromo unity by keeping them preoccupied with external conflicts, thereby eliminating any coordinated opposition within Oromia itself.

This approach, however, has sown deep distrust across Ethiopia. Other ethnic groups increasingly see his government as an “Oromo government” rather than a national one. This perception weakens Abiy’s position—if war erupts again with Tigray or other forces, many groups might refuse to fight for him, fearing that if he wins, they will have no chance of resisting Oromo territorial expansion.

Now, as Ethiopia teeters on the brink, Abiy finds himself isolated—distrusted by all and supported by none.

- The Political Opposition: Powerless and Irrelevant

Ethiopia’s opposition remains divided, weak, and ineffective against the incumbent government, which has the entire state apparatus at its disposal. While opposition parties have rejected the government-sponsored National Dialogue, their disorganization and lack of capacity for mass mobilization have left them powerless and politically impotent. Even if elections were held, the opposition is not sufficiently organized to compete and wrest power from the ruling party.

Although numerous opposition parties exist on the NEBE’s list of registered parties, they lack operational structures in major regions like Oromia, Amhara, and Tigray, which remain conflict zones. Opposition leaders are either exiled, imprisoned, or too fragmented to present a compelling alternative. Without a clear vision or unified leadership, they fail to inspire confidence, leading disillusioned youth to abandon politics in favor of armed struggle.

With no credible electoral path forward, the only credible opposition to Abiy Ahmed’s power comes from insurgencies rather than registered political parties, leaving Ethiopia without a legitimate democratic alternative.

- The TDF Factor: A Strategic Recalibration

The TDF remains Ethiopia’s most disciplined and experienced fighting force. However, since the Pretoria Agreement, they have been largely sidelined—a reality that may soon change.

Fanno and the OLA, realizing their inability to defeat the ENDF independently, may seek tactical coordination with the TDF. In the event of a conflict with the TDF, the ENDF would be forced to fight on multiple fronts. Already a hollowed-out military, the ENDF would be stretched thin in terms of both deployment and logistics, rendering it unable to supply its fighting forces adequately. This situation would likely intensify the rate of desertion and give insurgents a battlefield advantage, shifting the balance of power in their favor.

The prime minister, who has long used war as a vehicle for power consolidation, would, for the first time since his accession to power, see his grip on authority weaken, accelerating his potential downfall.

However, the TDF faces internal challenges. Unlike in past wars, it lacks strategic political leaders capable of bridging the gap between military success and governance. The recent rift within the TPLF leadership has further weakened its political direction. Nevertheless, another round of conflict with the federal government would revive memories of the last war, forcing them to recognize that their only path to survival is to set aside internal differences and unite against a common existential threat.

While Abiy’s forces are crumbling from exhaustion and internal defections, TDF’s ability to consolidate its ranks will determine its role in the next phase of the war.

- Prime Minister Abiy’s Crumbling Regime: Illusion of Power, Reality of Weakness

Abiy Ahmed projects the image of an all-powerful leader, but in reality, his grip on Ethiopia is rapidly weakening. His control is largely confined to the Republican Guard (20,000 elite troops), Addis Ababa, and federal revenue streams—which he spends with zero accountability. Beyond that, his authority is eroding across the country. Even these levers of power are slipping.

Tax collection has collapsed due to widespread conflict, depriving his government of critical funds. Key economic sectors—mining, construction, and agriculture—are in a freefall. Gold mining sites in Tigray, Oromia, Benishangul, and the South are either controlled by generals, insurgents, or, in some cases, even by South Sudanese and Kenyan forces. The construction sector is paralyzed, except for vanity projects like his $10 billion palace and corridor developments. The agriculture sector is equally devastated, with coffee exports from Wallagga plunging by 50% due to conflict.

Even his own Prosperity Party (PP) is fracturing. Regional governments act independently, most PP cadres disrespect him, and its 15 million members provide no financial support. To fund party operations, Abiy has resorted to forcing business owners to pay a 5% levy on bank loans. His governance thrives on fear and patronage, with over 90 ministerial reshuffles in six years, preventing officials from gaining expertise and ensuring absolute dependence on him.

Despite massive military spending, Abiy’s war machine is collapsing. His greatest weakness is the loss of experienced military leadership. Eritrean generals and strategists, who previously played a crucial role in shaping battlefield tactics, are no longer advising him. Additionally, he has lost much of his mid-level officer corps in the Tigray war and the ongoing conflicts with Fanno and the OLA. Unlike in previous battles, a total siege is now impossible, as multiple supply routes remain open to insurgents.

His forces are stretched thin, simultaneously fighting in Oromia and Amhara. Morale is at an all-time low—soldiers are exhausted, unwilling to fight, and increasingly surrendering. Many ENDF prisoners of war, after being released by the TDF, were redeployed to fight Fanno and OLA, further increasing the likelihood of mass surrender.

Top military leaders fear betrayal and abandonment. Having witnessed how Syrian President Bashar al-Assad abandoned his generals, they worry that they, too, could be left to face charges of war crimes. In the event that Abiy absconds, some may be left with the prospect of negotiating surrender in exchange for amnesty. It is a dreadful option.

Abiy’s sole military advantage is air power, relying on drones and jets for tactical leverage. But no war is won by air power alone. Without a disciplined ground force or a stable power base, drones and jets may delay his downfall, but they cannot prevent it—his regime is living on borrowed time.

- The International Community

With Trump back in power, he has suggested Egypt accept the people of Gaza while he plans to develop a Riviera in Gaza, sweetening the deal with GERD negotiations. If war erupts, Egypt is likely to back the TDF, leveraging its ties with Eritrea to intervene in the conflict to shape the outcome in its favor. Sudan, viewing Prime Minister Abiy as a Rapid Support Force (RSF) ally, may once again support TDF. Meanwhile, China, a key investor and lender, sees Abiy as weak and may be hedging its bets on future Ethiopian leadership.

The only countries likely to continue supporting Abiy’s war effort are the UAE, Turkey, Iran, and North Korea. The UAE, having heavily invested in Abiy, is unlikely to abandon him outright. However, the country’s ability to extend support to Abiy at previous levels is diminishing, as it is already entangled in the Sudan conflict. If Bashar al-Assad’s sudden fall from power is any guide, it would be safe to assume that the UAE will not hesitate to cut its losses and retreat if its leaders determine that Prime Minister Abiy is unsalvageable.

In contrast, Turkey, Iran, and North Korea are more transactional, likely to sell drones and military equipment in exchange for cash rather than a commitment to sustaining Abiy in power at any cost. If they determine Ethiopia lacks the financial resources to pay upfront for military supplies, these countries would have no qualms about leaving Abiy to his own devices.

What should be done?

Ethiopia’s future hinges on two key factors: the removal of Abiy Ahmed and the establishment of a transitional framework that would prevent the country from collapsing into further war and division. The following steps are essential:

- Ending Abiy’s Rule through Strategic Coordination

- Abiy’s rule has become a source of perpetual conflict, and no meaningful change can occur while he remains in power. The opposition must recognize that removing Abiy is a necessity, not an option, to return the country to the path of peace and democratization.

- The TDF, OLA, Fanno, ONLF, and other forces must set aside past grievances and coordinate their military and political efforts. Abiy thrives on sowing division and discord, and unless the opposition forces unite, his rule will persist.

- A structured resistance strategy must include simultaneous offensives, economic pressure, and diplomatic engagement to weaken Abiy’s control from multiple fronts.

- Preventing Ethiopia’s Collapse through Stakeholder Dialogue

- While the armed groups can contribute to ending Abiy’s rule, governance cannot be established by armed groups and military prowess alone. A post-Abiy transition must include dialogue among key ethnic and political factions to avoid repeating past cycles of exclusionary rule.

- Dialogue must begin immediately to address the deep mistrust and tensions between the Oromo elite and the Amhara and Tigray. Additionally, efforts should be made to reduce both tensions and mistrust between Tigray and Amhara, as well as between Tigray and Eritrea.

- Prominent Oromo leaders have long ago declared Abiy Ahmed unfit to lead Ethiopia, rejected his vision for the country, and opposed his endless wars and atrocities. Because they are uniquely positioned to expose his crimes with credibility, they must redouble their effort to delegitimize his claims of leading an “Oromo government” and invocation of his Oromo identity when he runs into political trouble. Their effort will pave a wide vista for other opponents to intensify their struggle and to collaborate with them in constructing a post-Abiy government.

- A broad-based national conference should be convened to establish a framework for a transitional governing arrangement, ensuring that all major stakeholders—including non-military actors—have a role in shaping Ethiopia’s future.

- Immediate efforts must be made to stabilize the economy, address humanitarian crises, and rebuild key institutions to prevent post-Abiy Ethiopia from becoming another failed state.

- Engaging the International Community to support a Managed Transition

- The opposition must actively engage regional and global actors, including the African Union, the United Nations, and influential states such as the U.S., Egypt, and the Gulf nations, to gain diplomatic support and legitimacy.

- Economic guarantees and security assurances will be necessary to prevent external powers from exploiting Ethiopia’s instability for their own geopolitical interests.

- Eritrea’s evolving stance presents an opportunity to shift regional dynamics. If Eritrea sees Abiy as a liability, Asmara would not come to his rescue. Opposition forces must refrain from taking actions that can provoke Eritrea into siding with Abiy.

A transition away from Abiy must be carefully managed to ensure Ethiopia does not fall into a power vacuum, which could lead to further violence. Coordination, both militarily and politically, is the only way to navigate this moment of crisis.

Conclusion

It is no longer plausible to expect Ethiopia’s future will be determined by elections or political reforms under Abiy Ahmed’s rule. His government has closed off all democratic avenues, leaving forceful removal as the only realistic path to change. However, while military resistance is an undeniable reality, it must be coupled with an inclusive strategy that prevents further fragmentation of the state.

The opposition must not only unite to remove Abiy but also take responsibility for crafting a new political order. This requires strategic coordination, stakeholder dialogue, and international engagement. Ethiopia has already suffered too much from cycles of war and authoritarianism—this transition must break the pattern.

The road ahead is difficult, but the choice is clear: either Ethiopia remains trapped in endless repression and war, or its opposition forces rise to the occasion, dismantle Abiy’s regime, and lay the foundations for a new, more inclusive future. The time for hesitation has passed. The time for decisive action is now.

Footnotes

We need your support

We trust you found something of value in this article. If so, we kindly ask you to consider helping Curate Oromia continue its work.

If you believe in the importance of independent voices and honest reporting, we invite you to support our efforts through our GoFundMe campaign.

Every contribution, however small, goes directly to our writers and the expansion of our reach.

Thank you for your support.